[flagallery gid=17 name=Gallery]

Here are some Belgian Movie Posters. Which one do you like best? How do you like them in general? If you have some more, please add them. Thanks!

— Inga

[flagallery gid=17 name=Gallery]

Here are some Belgian Movie Posters. Which one do you like best? How do you like them in general? If you have some more, please add them. Thanks!

— Inga

— David DeWitt

While I was searching for the rules of this blog I happened to notice the section labeled admin and saw that your birthday was yesterday. So may I wish you, David a belated a happy birthday and tell you what a wonderful job you are doing. And to wish you many more happy years!–A. R.

— ILIKEFLYNN

With the arrival of the auteur theory, filmmakers like Michael Curtiz no longer get as much sway among the current generation of directors. Curtiz (born Kertész Kaminer Manó in Hungary in 1886), was a journeyman, a man who flourished in the studio system after being picked out by Jack Warner for his Austrian Biblical epic “Moon of Israel” in 1924. He stayed at the studio for nearly 20 years, taking on whatever he was assigned at a terrifyingly prolific rate — he made over 100 Hollywood movies up to “The Comancheros” in 1961. And some of them are terrible, as you might expect.

But Curtiz was also responsible for some of the greatest films of the era, and those who diminish his abilities (including the director himself, who once said “Who cares about character? I make it go so fast nobody notices”) are ignoring his enormous skill behind the camera, and his undeniable capacity for getting great performances out of some of the biggest stars in history. And slowly, his reputation has been restored over time — Steven Soderbergh (who, coincidentally, joins Curtiz as one of only two filmmakers to pick up two Best Director Oscar nominations in the same year; Curtiz for “Angels With Dirty Faces” and “Four Daughters,” Soderbergh for “Traffic” and “Erin Brockovich“) has praised his work, and the younger filmmaker’s “The Good German” is in many ways a tribute to his forerunner.

Curtiz died fifty years ago today, on April 10th 1962, and to commemorate the anniversary, we’ve picked out five of the director’s finest works as a starting point for those who want to dig into his wider career. There’s plenty more gems where these came from — the filmmaker was incredibly versatile, ranging from action-adventure to musicals, comedies to melodrama — but these are the five highlights of a colossal output.

“The Adventures of Robin Hood” (1938)

In 1935, Curtiz had helped popularize and legitimize the cinematic swashbuckler with “Captain Blood,” a thrilling pirate tale that picked up a Best Picture Oscar nomination, and saw Curtiz come second in the director category, despite not having been nominated (write-in votes still held some power back then…) Three years later, Curtiz returned to the big screen, along with his ‘Blood’ stars Errol Flynn (who would become a favorite of the filmmaker: this was their second of twelve collaborations) and Olivia De Haviland, having refined and perfected the formula, with “The Adventures of Robin Hood.” In fact, Flynn wasn’t the first choice: Jimmy Cagney had originally been targeted for the part, but left Warners, causing a huge delay until Flynn eventually took over. And it’s hard to imagine anyone else in the part: Flynn’s roguish charm and sheer pleasure in his adventures (a far cry from the joyless takes by Kevin Costner or Russell Crowe) has defined Robin Hood for generations to come. And his supporting cast are absolutely his match — de Havilland is sweet as Marion, and having Basil Rathbone and Claude Rains as the pair of sniveling villains is pretty much an unmatchable combination (it’s like having Gary Oldman and Alan Rickman playing a duo of evildoers today). Despite the attempts of Costner and Ridley Scott over the years, this is still the definitive cinematic take on the British outlaw who robs from the rich to give to the poor, with genuinely glorious Technicolor (the film was only the studio’s second experiment with color at the time), and action sequences as thrilling as anything that’s ever been seen on screen — principally because so much is done for real, right down to the famous scene of the arrow being split in two (albeit aided by bamboo arrows and wires). It’s perhaps too sincere and irony-free for contemporary audiences, but it remains one of best action-adventure movies in cinematic history.

“Angels With Dirty Faces” (1938)

The dawning of the Production Code era meant that, however popular the gangster picture was, it would always end the same way: the antihero would meet his demise, normally through a hail of bullets, to demonstrate to the audience that crime didn’t pay. But that ending’s rarely been pulled off with as much a sense of genuine tragedy as Curtiz managed with “Angels With Dirty Faces.” It’s a familiar tale by now, following two kids from the wrong side of the tracks who take divergent paths. After Rocky (James Cagney) takes the fall for a streetcar robbery pulled with his pal Jerry (the actor’s great friend Pat O’Brien, who would co-star in nine films across nearly forty-five years, up to 1981’s “Ragtime“), the former would grow up to be a powerful mobster, the latter a priest, trying to keep kids — played by the young actors who would go on to be the Dead End Kids/Bowery Boys — on the straight-and-narrow. But Jerry’s drawn back in when Rocky comes up against a pair of sinister businessmen, Frazier (Humphrey Bogart) and Keefer (George Bancroft); Rocky kills them when they target Jerry, who’s about to expose their corruption, and is sentenced to death. To stop his death becoming a martyrdom to the kids, Jerry persuades Rocky to go the electric chair as a coward, and he dies screaming. It’s undoubtedly moralistic, but the relationship between Cagney and O’Brien feels so etched in truth that it carries a weight and heft that’s rare for even the golden era of gangster movies. Curtiz is in fine, noirish form, particular in the climactic shootout, and the rat-a-tat script (thanks in part to a polish from Ben Hecht andCharles MacArthur) remains eminently quotable.

“The Sea Wolf” (1941)

Never released on DVD in the U.S., and mostly forgotten by this point, surviving principally through rare TV airings, Curtiz’s adaptation of Jack London‘s sea-set adventure is probably the best candidate for the hidden gem of the director’s filmography. The story follows a writer (Alexander Knox) and an escaped convict (Ida Lupino, excellent as a character invented for the screen by writer Robert Rossen of “All The King’s Men” and “The Hustler” fame), who are caught in a shipwreck, and retrieved by the tyrannical Captain Wolf Larsen (Edward G. Robinson), who faces mutiny from his cabin boy, George Leach (John Garfield). Rossen’s script is a model of great adaptation, departing from London’s text to make it more cinematic while still capturing its spirit and its characters, and given it was released as the Second World War was underway, Larsen’s near-fascistic figurehead has a resonance that still rings today. It’s one of Curtiz’s most complex works — a world away from another Flynn vehicle, swashbuckler “The Sea Hawk,” which landed the year before — with a psychological realism that would pave the way towards the likes of “Mildred Pierce.” And once more, there’s a titanic star performance at its center. Edward G. Robinson was best known for gangster movies like his star turn in “Little Caesar,” but he gives arguably his finest performance here as Larsen, a complex monster who isn’t without his moments of sympathy; his final scene, blind and raging, going down with the boat, is staggeringly brilliant work. The film suffers a little from a rather bland protagonist in Alexander Knox, but for the most part it’s a forgotten classic that we hope turns up on the Warner Archive sooner rather than later.

“Casablanca” (1942)

Based on a play that was, by all accounts, pretty terrible, and made under a frantic production that had a well-documented casting back-and-forth, few expected “Casablanca” to be anything but a forgettable programmer, a cash-in on the now-overshadowed 1938 box office hit “Algiers.” That it became a Best Picture winner (and responsible for Curtiz’s only directing Oscar), and one of the greatest American movies ever made, is a case of how, every so often, the stars align just in the right way. Because “Casablanca” is perfect across the board: a rich, gripping story, told through a script that never puts a foot wrong forward (thanks to the Epstein Brothers,Howard Koch and an uncredited Casey Robinson), helmed with uncanny sense of pace and tone by Curtiz and performed by a colorful, charismatic cast that once more showed the director’s capacity for picking the right face for a part (has any supporting cast ever matched the likes of Claude Rains, Conrad Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre here?). And the film is a tricky balancing act, because it has everything that you could want in a movie — comedy, thrills, a great love story — but it takes a craftsman in the best sense of the word to make the elements work in harmony, and one can only wonder what would have happened if original choice, William Wyler, had helmed the film instead. Technically, it’s superb too: DoPArthur Edeson, who was also behind “The Maltese Falcon” and “Frankenstein,” was perhaps the finest cinematographer working at the time, and he lights Ingrid Bergman perhaps better than anyone’s ever lit a star, while giving the North African setting an unforgettable noirish tinge. If you’ve somehow never seen it, drop whatever you’re doing and fix that.

“Mildred Pierce” (1945)

By 1945, Joan Crawford had been a star for twenty years, but wasn’t exactly at the peak of her career: she’d been labeled as box office poison in 1937, and was bought out of her contract by MGM for $100,000. She went across town to Warner Bros in 1943, wanting to star in a movie version of “Ethan Frome,” but when that film didn’t happen, she stepped in for nemesis Bette Davis on an adaptation of James M. Cain‘s “Mildred Pierce,” despite the initial objections of Curtiz, who had to be convinced by a screen test. But the gamble paid off in a big way in the film that sees Crawford play a self-made woman, the owner of a chain of restaurants, tormented by her horrible little shit of a social-climbing daughter. It proved to be a major hit, and Crawford won a Best Actress Academy Award, putting her right back on top again. And even in light of Todd Haynes‘ five-hour HBOminiseries last year, an excellent, religiously faithful take on the same material that dumps the noirish murder subplot, Curtiz’s film holds up today in a big way. The director’s expressionistic experiments in light and shadow reach their apex here, with a flashback structure that feels like a knowing nod at “Citizen Kane,” and as ever, the cast is immaculate, and the pacing moves along at a neat clip. But ultimately, it’s Crawford’s show, and she’s phenomenal in the film. Her hunger to get back on top is almost palpable, but there’s little ego to the performance, with a maternal love that had rarely been seen from the actress before, and a true heartbreak when she sees how little gratitude her little monster Veda (Ann Blyth) has for her. As superb as Kate Winslet was in Haynes’ version, it’s always going to be Crawford that’s associated with the role.

Honorable Mentions: Most of his pictures with Flynn, including the aforementioned “Captain Blood,” “Charge of the Light Brigade,” “Dodge City,” “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex” and “Sante Fe Trail,” are worth checking out, while his Oscar nominated work on musical “Four Daughters” is pleasant entertainment (as are “White Christmas” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” the latter of which has dated a little, but features a brilliant performance from James Cagney). He also virtually invented the sitcom, in big-screen form, with William Powell in “Life With Father” and helmed one of Elvis Presley‘s best films, “King Creole.”

— tassie devil

April16th!

April16th!

Date: Thu, 12 Apr 2012 23:01:47 -0400 (EDT)

Hi folks,

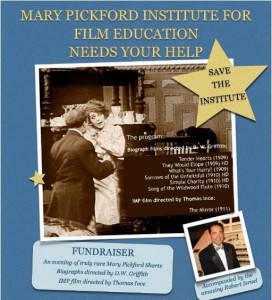

Please come to our Biograph night at the Mary Pickford Studio this coming

Monday. I think I can guarantee that you won’t have seen more than two of

the seven shorts we’re showing, if that! Live music by Robert Israel.

Help us save the Institute!!!! Donations accepted!!! The TCM festival will

be over, so join us for a memorable Monday! Digital projection, with three

titles from custom blu-ray disks. Take a look!

Thanks to Karl Holmberg!

— David DeWitt