Australian Women’s Weekly

Comeback for the Fabulous Flynn

— Tim

December 22, 1938

Basil Rathbone today seemed destined to play another of the “heavy” roles that have made im one of the screen’s most famed menaces. Hal Wallis i negotiating a deal with Rathbone, wherein he would play the part of Lord Wolfington in The Sea Hawk.

Errol Flynn already has been announced for the star role in the picture, which will be Seton I. Miller’s revision of the Raphael Sabatini thriller. Rathbone, as Queen Elizabeth’s advisor, was in mind when Miller wrote the script.

If the deal goes through, this will be the fourth picture in which Flynn and Rathbone have played together. The other three are Captain Blood, Robin Hood, and The Dawn Patrol. Michael Curtiz probably will direct The Sea Hawk. He piloted Captain Blood.

…

Has any fencing menace ever fought better, or died better, than Basil Rathbone? I think not.

(Certainly not Henry Daniell!)

— Tim

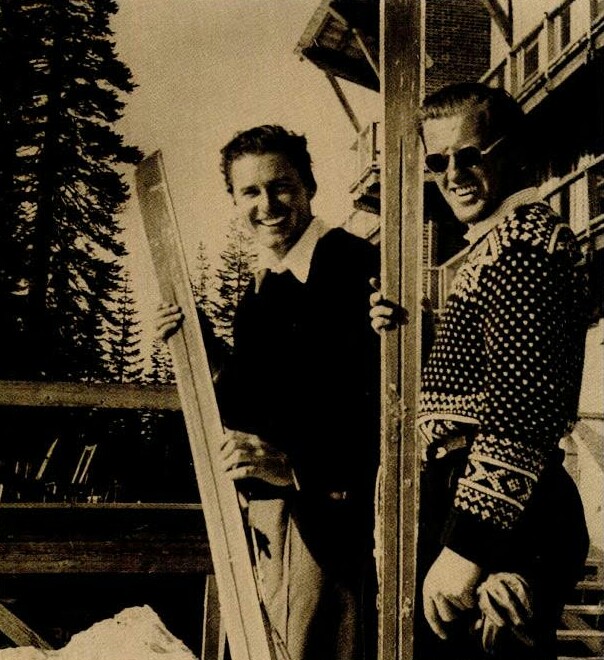

On December 21, 1936 – 84 years ago today – Errol attended the legendary grand opening of the Sugar Bowl.

“The winter playground for many actors when it first opened, Sugar Bowl ski resort frequently welcomed Errol Flynn, who liked to sit on the porch of the popular lodge. He reportedly soaked up the sun while also keeping a close eye on the ladies.”

“Women often walked by in amazement, finding it difficult to believe the famed Hollywood playboy was in their midst. Girl-watching might have been Flynn’s favorite pastime, but the rumor mill indicates the swashbuckling actor was a fairly gifted skier as well.”

With famed skier, Hannes Schroll

— Tim

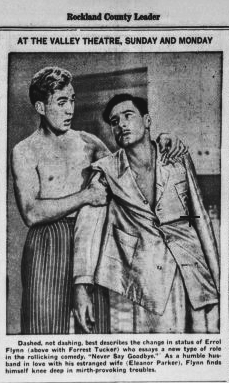

“Dashed, Not Dashing – A New Type of Role” for Errol

December 22, 1946

— Tim

December 20, 2008

The Hollywood Immortals Who were Made by Blood

Flynn, De Havilland, Korngold

Errol Flynn: His sword carved his name across the continents – and his glory across the seas!

Flynn had only moderate acting experience. His roles in the four films he made since 1933 were small and somewhat unimpressive. Who remembers him as Fletcher Christian, for example. But he improved so rapidly in Blood that many early scenes were reshot. In fact, he ends up being quite good on screen, giving the impression of understanding his role, approaching his part, maybe, with the care of a Shakespearean actor. It’s a common appraisal but true: besides being able to flourish a sword better than anyone before or since, Flynn wore period clothes with style, as if he had stepped out of the past, or, as some have said, belonged there.

He spoke the convoluted lines naturally and with conviction. Not easy. The stilted quaintness and archaisms of the dialogue are largely retained from Rafael Sabatini’s 1922 novel, thanks to Casey Robinson’s screenplay. Yes, the words have a certain fascination because they are so quaint, so different from normal usage and seem to fit imagined 17th-century speech: “Faith, yes, I don’t doubt it. You’ve the looks and manners of a hangman.” “It’s entirely innocent I am.” “Bedad, we’ll have a crew yet!” “ … while I, who hate this pestilential island—well, such are the quirks of circumstance.” —All lines delivered by Flynn!

Olivia de Havilland: Her talent, beauty and charisma were resplendent

As for Olivia de Havilland, who had made only one previous film, A Midsummer Night’s Dream earlier that year, Blood offered a much larger role. Her girlish and virginal persona would endure essentially unchanged in the seven subsequent films she made with Flynn, and the two would become one of Hollywood’s great romantic screen couples, á la Tracy and Hepburn, Bogart and Bacall. The charisma between the two, immediately evident in Blood, persists resplendently in all their films.

Erich Korngold: His film scoring changed everything

A Viennese composer of operas and chamber music, once a child prodigy, Korngold had worked with de Havilland on the Shakespeare movie arranging Mendelssohn’s music. Warner Bros. was so impressed they asked him to write an original score for a “little” movie they had just finished. Korngold, without seeing Blood, said no, but after WB’s insistence and a private screening, he was so moved by the film’s charm and humor* that he agreed to write the music.

The humor that so impressed Korngold runs throughout the film. A recurring joke is Governor Steed’s (George Hassell) bout with the gout. Following a slave branding, the next shot shows the governor in a close-up. “What a cruel shame,” he says, “that any man is made to suffer so.”

What Korngold didn’t know—what WB had failed to tell him—was that he had only three weeks.

With time running out, he borrowed parts of two Franz Liszt tone poems, Mazeppa and Prometheus, to support the noisy battle scenes, interspersed with previous Korngold music from the film. While movie composers today appropriate the classics as their own, usually without acknowledgment, Korngold insisted his main title credit read “Arrangements by Erich Wolfgang Korngold.” This automatically disqualified Blood for nomination as Best Score, which it surely would have received; the composer would win the next year for Anthony Adverse.

Korngold had a large part—a very large part—in the overwhelming success of Captain Blood. A contemporary equivalent would be John Williams’ impact with Jaws (1975) or, even more so, the first of the Star Wars films (1977), which, in fact, is an obvious homage to the Korngoldian style—the lyrical, richly orchestrated, heart-on-sleeve ardor of 19th-century music.

Audiences who first heard Blood were astounded. They had never heard such music, not even compared with Max Steiner’s ground breaking King Kong (1933). The orchestra which recorded the music to film, the studio heads who saw the completed movie before release and the public which attended the country’s theaters—none of them had ever heard such music from a motion picture—a large orchestra by studio standards, complicated orchestration, big, luscious sound, dramatic music that perfectly underpinned the screen. Blood remains a milestone in film scoring, and Korngold would contribute to six more Flynn films.

Blood and his crew setting sail from Port Royal is one of the most lingering images in the film. He and Arabella exchange forlorn glances, he from the ship, she from shore, captured in multiple dissolves and supported by Korngold’s swelling music, horns echoing at the conclusion. (The scene, by the way, is replicated in The Sea Hawk [1940], Korngold and Flynn in tandem, only with Brenda Marshall as a pale stand-in for Olivia.) Later, before the final sea battle, when Arabella is put ashore in a longboat, there’s a reprise of that first separation, the two again staring after each other, if not to swelling, then certainly to lushly romantic music—horns again prominent.

Most critics say that as early as Anthony Adverse and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) Korngold began experimenting with pitching the key of the music just beneath the actors’ voices. It began, actually, with Blood, if not sooner. Perhaps the best example, in any of his film scores, of how he unifies music with the screen image is the pillory scene between Blood and Jeremy Pitt (Ross Alexander), how the music—the second theme—changes in ambience, orchestration and volume, according to the emotions of the two men. Likewise, in the final love scene (“Whom else would I love?” Arabella asks), the music hesitates, softens, speeds up, becomes richer or changes in instrumentation, even disappears at one point, based on the tempo and emotion of the dialogue.

Thank you, Maestro Korngold, for this and all the your magnificent film scores. Your reward: The new career that save your life and the lives of your family.

.

And thank you, Errolivia, for the greatest swashbuckler and for being the most romantic co-stars in the history of Hollywood. Your reward: This kiss:

— Tim

One of the actors in the Escape Me Never photo below did something highly unusual on the set? Who was it and what was it?

— Tim

And “Best Popcorn Movie of the Mid-Thirties”

Released Eighty-Five Years Ago Today

December 19, 1935

…

— Tim

Want to be debonair like the swashbuckling Errol Flynn? First, grow a pencil mustache. Second, splash on some Cuir de Russie by Creed. It starts out lemony and then fades to sandalwood and leather. Unfortunately, this is the one cologne on the list that’s no longer available (at least you still got that pencil mustache), but the smell of Cuir de Russie was said to be reminiscent of standing in the boot section of a western wear store. Giddyup!

— Karl

…

December 17, 1941

New York Times

It is altogether fitting—and highly commendable, too —that the studio which gave us “The Story of Louis Pasteur” and “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet” should turn attention at this time to an experimental branch of medicine which is making remarkable strides and which is of tremendous importance to our preparations for defense. And this the Warners are doing in “Dive Bomber,” yesterday’s arrival at the Strand, which is less about dive bombing than it is about aviation medicine, less about the fellows who fight in airplanes than it is about the surgeons who fight the strange and unpredictable ailments that attack a flying man high in the blue. For its oddly dramatic subject and its most extraordinarily colorful contents, “Dive Bomber” takes the palm as the best of the new “service films” to date.

Colorful, indeed, is the word which should be most clearly emphasized, for not only do the modern experiments in aviation medicine, elaborately detailed herein, have unique and fascinating pictorial interest, but the Warners have photographed this picture in some of the most magnificent technicolor yet seen. And, naturally, they have not forgotten to turn the cameras often upon masses of brilliantly colored planes, ranked in impressive rows about an air base or upon the huge flight decks of carriers, and roaring in silver majesty, wing to wing, through the limitless West Coast skies.

Never before has an aviation film been so vivid in its images, conveyed such a sense of tangible solidity when it is showing us solid things or been so full of sunlight and clean air when the cameras are aloft. Except for a few badly matched shots, the job is well nigh perfect. And the story? Well, again we face a necessary evil. Frank Wead and Robert Buckner, who contrived the fanciful tale, were laboring under the old Hollywood notion that no man can be a hero (or a genius) without first being misunderstood. And they have made this a universal rule. Thus their young naval surgeon, around whom the story is built, is originally misunderstood by a couple of pilots whose injured pal irretrievably dies under his knife. Then the young surgeon, inspired to take up aviation medicine because of this, misunderstands the older doctor under whom he is placed for instruction. A new recruit for naval training is misunderstood by almost every one. And it takes the devil of a lot of brawling and passing of dirty looks before these fellows all get together to experiment in harmony on means to prevent the unconsciousness which comes at the end of a power dive and the deadly sickness which attacks pilots at high altitudes. When they do get down to business, however, it is fascinating to watch them work, and their experiments in pressure chambers and in the air are more exciting than any fights.

Naturally—or, perhaps, inevitably—there has to be a touch of self-sacrifice, and this comes at the end of the picture, rather patly but without too much offense. And, to the credit of the writers, it must be said that they have trimmed romantic dalliance to the core. A female is dragged into the picture only long enough to assure Errol Flynn of holding his franchise as a wolf. For it is Mr. Flynn who plays the young surgeon, and he does so with his usual elegance, looking very dashing and romantic in a variety of uniforms and behaving with solemn dignity in moments of stress. Fred MacMurray and Regis Toomey play a couple of hard-bitten, old-line pilots credibly, and Ralph Bellamy gives a serious, impressive performance as an older doctor. In the few glimpses we have of her, Alexis Smith looks good; can’t tell you yet how she acts. But chief credit for the glory that’s in this picture goes to the United States Navy, which cooperated in its production, and to the fellows who aimed the cameras. They collectively gave it powerful and steady wings.

DIVE BOMBER; screen play by Frank Wead and Robert Buckner; from a story by Frank Wead; directed by Michael Curtiz for Warner Brothers. At the Strand. Doug Lee . . . . . Errol Flynn Joe Blake . . . . . Fred MacMurray Dr. Lance Rogers . . . . . Ralph Bellamy Linda Fisher . . . . . Alexis Smith Art Lyons . . . . . Robert Armstrong Tim Griffin . . . . . Regis Toomey Lucky James . . . . . Allen Jenkins John Thomas Anthony . . . . . Craig Stevens Chubby . . . . . Herbert Anderson Sr. Surgeon at San Diego . . . . . Moroni Olsen Mrs. James . . . . . Dennie Moore Swede Larson . . . . . Louis Jean Heydt Corps Man . . . . . Cliff Nazarro

— Tim