— Tina

Author Archive

Behind the scene of They Died With Their Boots On!

As we love to know the background of Errol’s movies here is one fascinating story of the making of They Died With Their Boots On.

Did you know that Jack Warner had the title first and liked it so much that he looked for a story to fit the title? Amazing! That’s Hollywood!

In addition, you know that Errol in his MWWW told us of an accidental death of an Extra-Rider in The Charge of the Light Brigade by the name of Bill Meade. Now you can find out who it really was and that he played Polo with Errol. Now we know that Errol also played Polo.

It is a long story but the information is astonishing and very worthwhile to read and to have it recorded on our blog as an important information. I hope you agree?

They Died With Their Boots On

by Dan Gagliasso

American Cinematographer

Legendary director Raoul Walsh claimed that in the fall of 1941, when studio head Jack Warner first viewed the spectacular “Last Stand” climax in Walsh’s They Died With Their Boots On, the mogul declared, “If Custer really died that way, then history should applaud him.” Walsh was often given to self-serving exaggeration, but the reaction of Warner’s good friend, media magnate William Randolph Hearst, was equally enthusiastic and well-recorded. After seeing the film in early December, Hearst wired Warner via Western Union: “GREATEST FILM I HAVE EVER SEEN. WENT TO SEE IT TWICE WITH MARION. RANDY.”

The influence of Errol Flynn’s colorful portrayal of George Armstrong Custer on several generations of film-goers is undeniable. If Custer’s image has been tarnished of late by revisionist historians who paint him as the very symbol of late 19th-century America’s sins against its native people, only a Sioux or a Cheyenne who was a sore winner could not respond to the wonderful imagery that Warner Bros. brought to the screen with Boots.

Custer’s final battle had been fertile fodder for numerous silent film treatments of the Little Big Horn incident, most notable Thomas Ince’s Custer’s Last Fight in 1912 and Universal’s sweeping 1926 rendition in The Flaming Frontier. Warners’ new entry would be the first of only a few subsequent attempts to film a full-blown biography, however inaccurate, of the controversial Civil War boy general and Indian fighter.

If it hadn’t been for Jack Warner’s friendship with publisher Hearst, however, They Died With Their Boots On might never have seen the dark of a theater. In December of 1939, as a favor to one of his Atlanta Georgian American editors, Thomas Riply, Hearst had written to Warner to recommend Riply’s modest-selling biography of Texas gunfighter John Wesly Hardin as possible film material.

Hearst’s personal interest in the material was a decided plus for the Atlanta editor, and it took less than a month for Warner to work out a deal with Riply’s Los Angeles-based agent. By January 20, 1940, Riply was depositing a $750 check in his bank account, courtesy of Warner Bros.

The studio’s story department didn’t seem to know what to do with the material; by all accounts, John Wesly Hardin was a charming but cold-blooded killer who, amongst other vicious deeds, delighted in gunning down black Texans and Hispanics with impunity. Story editors Richard Macauly and Jerry Wald advised Warners executive producer Hal Wallis that They Died With Their Boots On was a great title, but told him to forget about making Hardin the focal point of the film.

By July of that same year, Warner’s producer Robert Fellows, who would later become John Wayne’s successful producing partner for most of the 1950s, asked contract writers Aeneas Mackenzie and Wally Kline to search for a Western film subject suitable for the title They Died With Their Boots On. It took the duo three months to finally find and push for “a biographical film on Custer that climaxed with the Black Hills gold rush.” Make no mistake, the Black Hills gold rush, referred to in their notes, was synonymous with carrying the story all the way to the Last Stand. Producer Wallis gave them the okay to develop a treatment, and by December 5, 1940, he finally approved the writers to move on to a first-draft screenplay.

By March of 1941, without a completed screenplay in hand, Jack Warner was ready to commit the studio’s charismatic swashbuckler, Errol Flynn to the lead role as the buckskin-clad Custer. Warner himself noted that, “Flynn in modern clothes just doesn’t seem to go over… it seems the public only wants him in the outdoor productions we have been having him in.” Business on Flynn’s new contemporary film Footsteps in the Dark was down over 20 percent from his hugely successful period adventures, such as The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk.

By the time Mackenzie and Kline handed over their first draft in early May, it was obvious that they had given strong consideration to America’s almost inevitable involvement in the war that was already ravaging most of Europe and Asia. Kline advised producer Wallis that “all consideration was given to construct a story which would have the best possible effect upon public morale in these present days of impending national crisis. I need not mention that when this picture opens, thousands of youths will undoubtedly be being trained for officer’s commissions in hundreds of new and traditionless units which are even now being formed.”

Hence, the patriotic Kline and Mackenzie decided to focus their Custer script on the bond between an officer and a regiment. Kline went on further to explain to Wallis that “if we can inspire [U.S. soldiers] to appreciation of a great officer and a great regiment in their own service, we will have accomplished our mission. You will observe that through the action of They Died With Their Boots On, Custer is selfish and self-serving at first, but comes to the realization that the regiment means more than glory to him, and sees no other course open to him but to die at the head of his doomed squadron.” Kline’s assessment may not have been entirely accurate, but how could Wallis or Jack Warner resist such a pitch?

Meanwhile, the casting for Boots was falling nicely into place. In the role of Elizabeth Custer, Olivia de Havilland would portray Flynn’s love interest for the final time after seven previous and highly successful pairings, most notably in The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Charge of the Light Brigade. Her sister, Joan Fontaine, had been an early favorite for the part, but expressed little interest in playing second fiddle to Flynn’s derring-do.

Arthur Kennedy had won out over Robert Preston, Van Heflin and several others to play Custer’s ex-West Point antagonist, Ned Sharp. The film’s crusty frontier scout, California Joe, was originally to have been portrayed by Flynn’s regular sidekick, Alan Hale, but the part eventually went to the versatile character actor Charley Grapewine.

The character of Queen’s Own Butler, the English soldier of fortune who joins the Seventh, was originally based on the real historical figure Lieutenant W.W. Cooke, with a bit of colorful fellow Seventh Cavalryman Captain Myles Keogh thrown in for good measure. Writer Mackenzie began to worry that Cooke’s descendants in Toronto might take offense and sue because of a slightly bawdy drunk scene. Cooke thus became the fictional Butler, and G.P. Huntly was chosen for the role.

The part of rough-and-ready Sergeant Doolittle went to tough guy Joe Sawyer, while the role of Sioux Chief Crazy Horse was awarded to Anthony Quinn, the only actor seriously considered for the job.

Jack Warner was known to be a notorious spendthrift who always tried to cut budgets to the bone. While other studios were spending $2,000,000 or more on their prestige projects, Warner often brought in similar films for almost half that amount. Boots was originally budgeted at $1,000,000 on a 42-day shooting schedule. By comparison, Casablanca, which was made the same year, cost $950,000, while John Huston made The Maltese Falcon for $375,000! Of course, neither of those films had required large numbers of extras or big battle scenes.

Still, Warner could smell box office all over Boots. Unfortunately, his headstrong and often irresponsible lead, Flynn, was giving him problems. Not only was Flynn in the middle of a particularly nasty divorce trial with French actress Lili Damita, but he was also refusing to work again with Warners’ hard-nosed director of epic action, Michael Curtiz.

Flynn and Curtiz had battled on many previous successes for Warner, including Robin Hood, The Charge of the Light Brigade and Dodge City. Flynn had decided that he needed a bit more kid-glove handling than the very demanding Curtiz ever gave him.

To massage Flynn’s ego, Jack Warner diplomatically hired veteran director Raoul Walsh to direct Boots. (Olivia de Havilland had told Flynn that she’d just had a wonderful experience working with the respected filmmaker.) Walsh had helmed Douglas Fairbanks in the silent classic The Thief of Baghdad, but his subsequent successes with What Price Glory? and Carmen had left him resting on his laurels a bit. He was reestablishing his reputation, however, with hard-boiled gangster pictures such as Humphrey Bogart’s High Sierra.

Walsh was a man’s man who specialized in the action genre. Once, when a junior producer suggested to Warner that Walsh direct a tender love story, Warner snapped back, “Walsh’s idea of a tender love story is a bawdy-house burning down.” Nevertheless, on Boots, his skillful handling of the scenes between de Havilland’s Libbie Custer and Flynn’s George provided some of the most heartfelt moments in an otherwise energetic action film.

Walsh’s cinematographer on the show was one of the best in the business. Bert Glennon, ASC had done it all: he had been co-director of photography for Cecil B. De Mille in the 1920s, and had shot the silent version of The Ten Commandments. A favorite of John Ford’s, Glennon had just been nominated for an Academy Award for his work on Stagecoach the year before, and had recently worked for Ford on the impeccably photographed Young Mr. Lincoln. The cameraman’s involvement with anything relating to American Indians was especially appropriate; his fellow director of photography at De Mille’s in the Twenties was still photographer Edward S. Curtis, who was world-renowned for his magnificent portraits of late 19th-century native tribesmen.

According to Walsh, he and Glennon had a comfortable working relationship on the picture. “I’d take him out and ask how it would be for him if we’d shoot a particular scene here or there,” the director said. “If he wanted me to move 40 feet away and it didn’t affect the background, I’d move. And I always consulted him on his light.”

Occasionally, Walsh might ask Glennon which lens he was using. and “ask for a change from a two-inch to a 35mm or whatever.” By and large, though, Walsh respected Glennon’s expertise, and left the talented cameraman to his own devices. Glennon knew that Walsh loved low-angle shots — “side angles and real low angles just as though they were in a photographer’s gallery.” The experienced cinematographer had no problem satisfying both Walsh’s tastes and his own.

The start of filming was originally slated for June 25, the 65th anniversary of the Little Big Horn fight, but Flynn’s courtroom troubles pushed the start date back a week. On July 2, filming finally commenced in Stage 14 on the Warner Bros. lot with interior scenes that took place in Major Taipe’s West Point office.

Walsh always said that he shot the complete sequence of Custer’s Last Stand first, but a search of Warner Brothers’ extensive archives reveals otherwise. Most of July was spent filming scenes set in West Point, Washington, D.C. and Monroe, Michigan. Pasadena’s Busch Gardens stood in for the main gate of West Point, while other major building exteriors were shot on either the Warners lot in Burbank or the studio’s sprawling ranch in Calabasas, 10 miles away.

Art director John Hughes did an admirable job of constructing the exterior of the original Custer home, as well as the Seventh Cavalry’s head-quarters buildings at Fort Abraham Lincoln, on the studio’s ranch property. However, he did give in to convention when he enclosed part of the five-acre set with a log stockade and blockhouse. Still, the blockhouse was an almost exact duplicate of the one that existed at old Fort McKeen, only a few miles from the real Fort Lincoln.

By the end of July, it was time for Walsh to move on to some saber-clashing Civil War action. Top-notch second-unit director B. Reeves Eason was a magician at capturing exciting period cavalry battle scenes. He had been the impetus behind the thrilling climax in Flynn’s earlier film The Charge of the Light Brigade, and also lent his skills to the chariot race in the original Ben Hur.

In Boots, the Civil War sequences representing Bull Run and Hanover would utilize approximately 100 mounted extras. Walsh always maintained that he was saddled with inexperienced riders, and there may have been some truth to that complaint in terms of the Last Stand shots, which featured up to 200 mounted men. Indeed, three men lost their lives during the course of filming, prompting KFI radio personality Erskine Johnson to publicly criticize Warner Bros. One rider died of a heart attack while atop his mount, and another, George Murphy, drunkenly ignored instructions to give up his horse, then fell off and broke his neck.

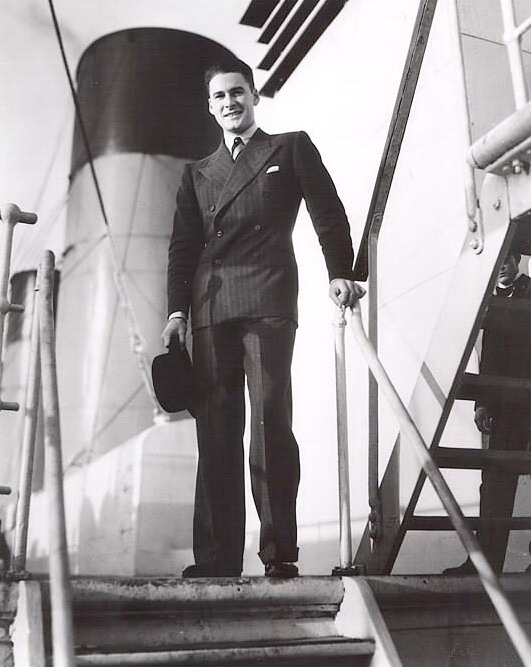

The third fatality was the most tragic. Ralph Budlong was a good polo player from Tucson who had not only just become a father, but was also worth close to a million dollars due to a recent inheritance. He was an experienced horseman who had often played polo against Flynn when the game was all the rage among such actors as Will Rogers, Spencer Tracy and Clark Gable. Budlong had insisted on using a real saber in the Bull Run bridge sequence, where the usual prop wooden saber would have sufficed, but a planned special effects explosion spooked his horse. According to the official inquest report eight days later, “his saber fell out of his hand at the time of his fall and apparently reached the ground hilt-first by the time Budlong came down on it.” Stuntman and Flynn crony Buster Willis helped rush the seriously injured man to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, where Budlong lingered for several days before dying from advanced peritonitis. In his autobiography, Flynn tells virtually the same story with the same background, except that someone named Bill Meade is the rider he claims was killed — during the filming of The Charge of the Light Brigade.

After Budlong’s death, the normally pugnacious Walsh may have been a bit skittish about exposing any other performers to the possibility of serious injury. He was soon making sounds about not using any falling horses in the upcoming battle scenes. In a memo dated August 1, production manager Mattison informed Walsh that Mr. Warner himself was insisting upon using falling horses in these scenes. Mattison then reported back to the studio head that stunt pay for the Last Stand sequence was going to be tremendous.

Stunt pay did prove to be exorbitant. The work was dangerous, fast and hard, but the cowboy stuntmen didn’t mind. Many of them wound up pulling down up to $250 a day, while the average working man at the time made $65 a week. Two of the stunt community’s best men doubled for the principals. The legendary Yakima Canutt stood in for Flynn, while John Ford’s future second-unit director, Cliff Lyons, doubled for Anthony Quinn as Crazy Horse.

The finished film reveals that Walsh may have gotten his way on the falling-horse issue. Unlike The Charge of the Light Brigade, for which numerous horses were killed doing fixed-wire falls, Boots exhibited none of the brutal-looking equestrian action that was so prevalent in pre-1940 films. There is reason to believe that Light Brigade’s excesses helped outlaw such falls well before They Died With Their Boots On went into production, and a Humane Society representative was on hand for at least a few days of filming.

One battle Jack Warner did win concerned the issue of where Custer’s Last Stand would actually be shot. Walsh wanted to film it among the polished rocks of the Iverson Ranch in Chatsworth, where the production had already captured several scenes of Custer’s wagon train and troops moving through Sioux territory.

Mattison and Robert Fellows advised Walsh that if they let him shoot there, “Mr. Warner would personally throw both of us in the alley.” There was no conceivable way the production would ever get the 400 men, 200 horses and necessary crew members onto the rock-strewn location Walsh had picked. It was finally agreed that Lasky Mesa in Agoura, located several miles west of the Calabasas Ranch and almost adjacent to Paramount Studios’ ranch, would serve as the site for the Last Stand sequence.

Walsh wanted some real Indians on hand to add authenticity to the film, so in early August, assistant Mace Littson was dispatched to the Standing Rock Agency near Fort Yates, North Dakota. He brought back 16 Sioux men who were willing to come play Hollywood for a few weeks for the princely sum of five dollars a day and expenses.

If Agency Superintendent L.C. Lippert had known what his charges were in for, he might not have agreed to the deal. Three of the Standing Rock Sioux were involved in a traffic accident that was not their fault, and Jack Red Bear wound up in the hospital for several weeks. The rest of the Sioux men were enjoying their Hollywood hotel and the local restaurants and nightspots, but weren’t so sure about the filming they were witnessing. No wonder: studio publicity claimed that two of them were the great-grandsons of revered Sioux leader Sitting Bull, who had helped rout Custer and his men that fateful day in 1876.

Filming on the complicated Last Stand sequence got underway on August 12, at which time the production was only five days behind schedule. In his memoirs, Walsh promoted the idea that most of his extras those first few days could hardly ride a horse. But according to Mattison’s studio reports, the production weeded out only about 30 of the 200 men who needed to be mounted. He then gratefully noted that all of the oldtime cowboys who were working offered to do their time as Indian riders, which the show sorely lacked in sufficient numbers.

Still, Mattison did comment that the injuries that occurred seemed to be sustained by the most experienced men, including old hands Al Delamore and Curly Gibson. As a practical joke, Anthony Quinn even hired a hearse to follow the extras’ buses out to Lasky Mesa. There were enough bumps, bruises and breaks to keep two ambulances, two doctors, four first-aid men and a nurse on hand at all times, and the production began to fall even further behind schedule.

During some of the shots, Walsh was directing Glennon, second assistant cameramen Ellsworth Fredricks (a future ASC fellow) and Benny Cohen while stationed high atop a massive 60-foot tower made of welded tubular steel. From this vantage point, the filmmakers captured some truly spectacular panoramic shots of Custer’s surrounded troopers being decimated by the Sioux warriors.

Flynn was out for several more days, due to his divorce court proceedings and a severe adverse sinus reaction to all of the smoke and dust being churned up during the vigorous battle scenes. Given all of the wide combat footage still to be filmed, however, it was easy to shoot around him. Flynn or no Flynn, the production was falling even further behind schedule.

Warners publicity chief Bob Taplinger was having a field day, trumpeting the presence of Sitting Bull’s relatives and floating a totally erroneous claim that Flynn was using Custer’s actual saber from Little Big Horn. Taplinger’s press release claimed that the good citizens of Custer City, South Dakota had loaned the production the rare relic. The sword in question was rare indeed, since as any Custer buff worth his buckskin jacket will tell you, historical record verifies that Custer and his men had left their sabers behind on that fateful day!

As the Last Stand scenes dragged on, the budget soared to the tune of almost $20,000 for each new day the production fell behind. With his newly-negotiated contract, Flynn alone cost $6,000 a week. But Jack Warner had taken a personal interest in the production, right down to making detailed lists of second-unit shots that he felt B. Reeves Eason needed to do. Included in Warner’s instructions were various pit shots, low angles, Akeley camera shots and mechanical horse scenes to feature some angles of Quinn’s Crazy Horse grasping the fallen Seventh Cavalry’s guidon.

By September 30, the cast and crew’s tribulations were behind them. At 5:15 p.m., after doing 23 setups with the second unit and several interior scenes of Flynn on Stage 6 back on the lot, shooting was wrapped. Boots officially wound up 26 days behind schedule and some $350,000 over budget. Editing, scoring and minor special effects, including one matte painting of the Indian village, took less than two months before Warners finally released the finished film to the theaters on December 1, 1941.

— Tina

Dodge City Trailer

A wonderful presentation of the premiere of “DODGE CITY” on April 1, 1939 in Dodge City Kansas

75 Years 1939 – 2014.

— Tina

An Anniversary Quiz!

There is a big anniversary this year! What is the anniversary and what did John Snyder say about it in 2012.

— Tina

A good Errol Quiz!

Errol had Family, Relatives, Friends galore and of course many acquaintances as we all know!

But who was Mike? That is the big question!

— Tina

What is that? Errol is in it!

And the clues are:

WHITE

TIGHT

CLASSIC

BRITISH

SMART

ELEGANT

REPRESENTING

Have fun guessing!

— Tina

Westerns Fighting Caravans 1931

I found this movie of Lili Damita and Gary Cooper from 1931 – Errol still in New Guinea – and I thought you maybe would like to see this movie.

Here it is:

— Tina