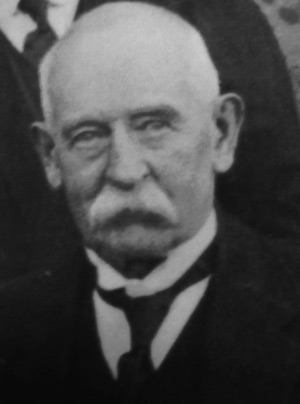

Theodore T Flynn

(1883-1968)

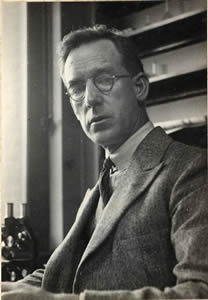

Theodore Thomson Flynn arrived in Hobart early in February 1909 to become the first lecturer in Biology at the University of Tasmania. He was born at Coraki in New South Waleson 11 October

1883 but moved to Sydney as a boy. he lived in Newtown very close to the University where he would later launch his career. When only fifteen he joined the State education Department as a pupil teacher and his first school was at Hillston in the far west of New South Wales. He won his first scholarship at the end of 1901 that earned him entry to Sydney Training College for Teachers,

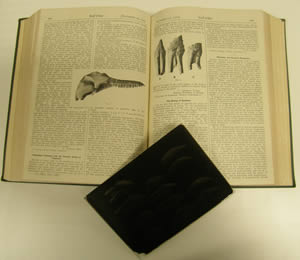

that was then attachedto Fort Street Model School. Further success there earned him another scholarship to study science at Sydney University. There he was a distinguished scholar, winning the John Coutts Scholarships, the Macleay Fellowship offered by the Linnean Society of NSW and the Medal for Biology in 1906. He formed a close friendship with a young lecturer James Peter Hill and two collaborated until Hill’s death in London 1954. After leaving university he held positionsas a science master in High Schools at Maitland and Newcastle then taught chemistry and physics at West Maitland Technical College. When appointed to the position in Tasmania he was Macleay Research Fellow at the Linnean Society of New South Wales.

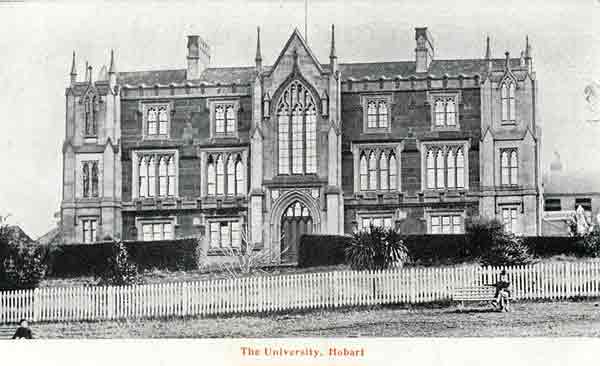

The University of Tasmania first considered a course in biology in 1906 when its Council appointed subcommittee chaired by Dr. E.L.Crowther to examine the matter. Crowther consulted

Melbourne University about the expected costs and with the Council’s approval approached the Premier for £300 a year to finance it. When the Government agreed to provideadditional funds Council agreed to implement the new course and placed an advertisement in the Melbourne Argus on 15 December 1908. Crowther’s Sub-Committeesubmitted the names of three applicants to the Council – Flynn and Ewen MacKinnon, who were both graduates of Sydney University, and A.E.V.Richardson of Adelaide. The Council judged them to be in that order, a significant accolade for Flynn

in the light of the illustrious later record of Sir Arthur Richardson in Australian science.

Although he eared that the salary of £250 per annum was barely adequate to cover his household costs, the appointment came at a most opportune time. A fortnight before leaving for Hobart

Flynn had married the beautiful and vivacious Lily Mary Young, the daughter of a Sydney based master mariner and descendant of Midshipman Young of the Bounty. Lily later changed her name to the more exotic Marelle. Flynn’s financial needs were exacerbated in June when his son Errol was born in Queen Alexander Hospital.

The erratic behaviour of both mother and son were to cause the biologist endless concern.

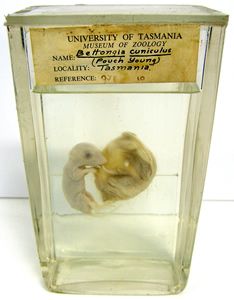

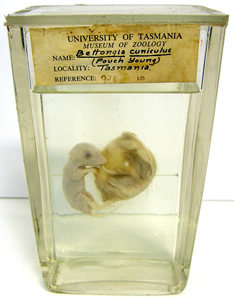

Flynn’s early research interests were in marsupials and soon after his arrival he joined the Field Naturalists Club on an Easter excursion to Wine Glass Bay. He was very industrious but also

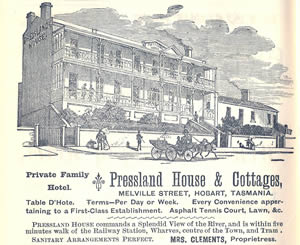

gregarious and friendly, enjoying dancing and tennis as well as his academic interests. A contemporary

observer described him as tall dark and ‘Irish’ in appearance and ‘active as a whipsnake’. Another said he was genial and students found his lectures interesting ‘he is one of thefew members of staff who sometimes attends University dances’. A fellow boarder at Pressland House in 1931 remembers him as ‘a very fine well groomed man’ who always wore a black bowler hat. He ‘took great pride in himself’, led a good life and ‘was greatly admired by the ladies of Hobart’. Errol remembered his father as lean, angular, full of charm and with a certain professorial quietness. He was certainly an industrious worker and totally committed to scientific research.

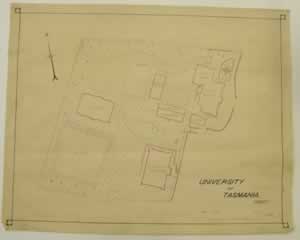

The University hurriedly built a new Department of Biology at the Domain site with three laboratories (one for Flynn and the others for teaching junior and senior students), a lecture room, a museum and an office for the professor. The building was heated and the benches covered in plate glass. A paved yard contained cages for animals and an area for plants. Flynn’s extravagant plans for the Department soon outstripped the budget forcing some revisions but resulted in a welcome increasein Government finance.

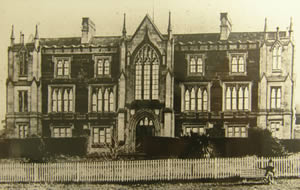

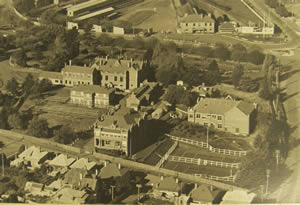

Right:

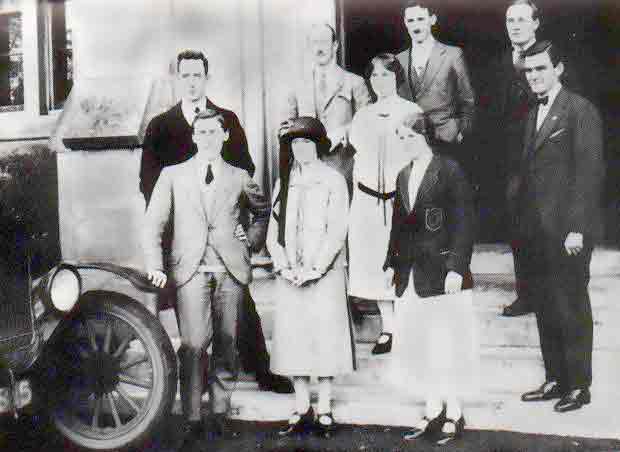

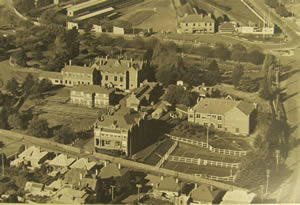

The University of Tasmania when Flynn arrived. Left Flynn with students (he is on the extreme left)

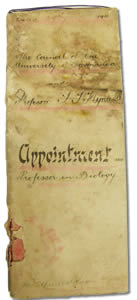

Flynn was initially appointed on a rolling one-year contract that was renewed in 1910 but the modest salary left him in a deteriorating financial situation. This position led him

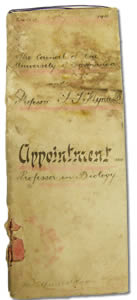

to tender his resignation at the end of January 1911. At the time the University Council was proposing to approached the trustees of the late John Ralston (1850-1908) of St Leonard’s Tasmania

seeking support for the University from funds set aside in the will for charitable purposes. The Council had a mind to establish a school of geology and these external funds would allow it to achieve its objective. It was also reluctant to lose Flynn and probably at the instigation of Crowther sought to use Ralston funds to boost the biology position to full professor. Flynn was sent to Launceston by the Council to join with Dr Crowther in discussions ith the Ralston Trustees. The result was the appointment of Flynn as the Ralston Professor of Biology in 1911, the fourth chair established by the University. The agreement with the Ralston Trustees provided £350 to establish a laboratory, £500 pa for salary and £100 pa for materials for three years. Flynn was allowed an annual vacation

from teaching of not less than 3 months and not less than one term free to undertake research. The research component was to be in:

‘(a) diseases of plants and animals, (b) anatomy and development of marsupials unique to Tasmania, (c) any other research approved by the Trustees.

In essence he had his salary doubled and had half the year free to pursue personal research; the generous nature of the position caused some envy amongst the staff. In 1921 a new agreement with the trustees provided £600 pa for 5 years for a professor of biology to research and added a new research interest when (b) was complete; (d) research on commercial food fisheries in Tasmania.’

Flynn joined the Royal Society of Tasmania and was elected a Trustee of the Museum and Botanical Gardens in 1911. In September 1912 he became Honorary Curator and appeared to act in that

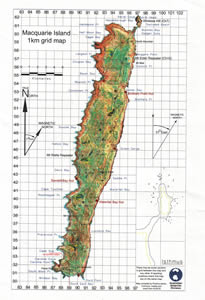

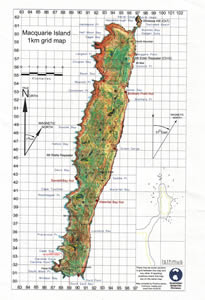

role until the appointment of Clive Lord late in 1918. During this time Flynn appeared to ignore any difference between the collections of the Museum and those of the University, a matter that caused some dispute after Lord took up his position. His interest in marine biology was broadened when he boarded Sir Douglas Mawson’s vessel the Aurora in November 1912. Flynn was the biologist

on a cruise from Hobart to Macquarie and Auckland Islands an Theo found his sea legs in the first nine days when the Aurora battled southerly gales. Thankful to arrive he telegraphed Lily and wrote a letter to his brother-in-law in Sydney.

In 1914 Flynn was elected to the committee of the University Progress Association this brought him into contact with Lyndhurst Giblin which in turn led to Joseph Lyons and the Labor Party.

The efforts of the Association produced an expansion of staff, one of the new lecturers being a Melbourne Economist, Morris Miller. Another eminent economist Douglas Copland joined the staff in 1916 and his protege, Torliev Hytten, formed a firm friendship with Flynn.

Fisheries Commissioner

Flynn’s association with these economists and their Labor Party connections inevitably drew the professor deeper into public policy. His interest in marsupials and membership of the Field Naturalists

made him a leading figure in the conservation movement. At the end of 1914 the country was then at war ‘with a relentless foe’ and was entering ‘the most serious drought yet experienced….and thus the resources of the State were not as buoyant as could be desired’. Tasmania had a new Labor Government led by John Earle with Joseph Lyons as Treasurer. Lyons took a keen interest in fisheries, one of his first Parliamentary roles was in a Select Committee investigating the legalization of pots in the lobster fishery. The election of the Labor Government drew Flynn into public life. One of the many

community functions to aid the War effort was Carnival Queen competition run the Lord Mayor of Hobart. Enid Lyons, the new wife of the Premier, was one of the entrants and accompanied by six year old Errol Flynn. When three positions on the Fisheries Commission became vacant the Government appointed Flynn.

When Parliament resumed in June 1915 the War, the drought and the condition of the State’s finances restricted the introduction of the reforms. Cabinet had discussed fisheries in December 1914 and it now got a request from the Fisheries Commissioners for an inquiryinto the supply and price of fish. As result a Royal Commission was issued to Flynn. Because the Chief Secretary Ogden was reported to favour a state rawler Flynn included in the inquiry a study of the stateowned trawlers in New South Wales.

Flynn exhaustively reviewed

Tasmanian fisheries and found –

‘The fishing industry has always languished in the State of Tasmania. No attempt has ever been made, except in a spasmodic way, to exploit in any large commercial way the vast resources of fish that

exist in most easily accessible grounds along the Tasmanian coast. No island State has ever yet reached full development without the thorough exploitation of its fishing resources’

He was now convinced that there was ‘ample possibility of supplying the Tasmanian public with large quantities of this delicate and highly nutritious food,’ and to ‘export to the ready market of the mainland’, and still allow ‘sufficient supplies for local canning, smoking, and curing establishments.’

Flynn found the chief obstacles to development to be restrictions on the use of some forms of fishing gear, the absence of large vessels and a lack of ‘technical knowledge’. Fishermen needed instruction i n new fishing methods and advice on the ‘movement and migration of fish’. A ‘Government Department responsible to the Minister’ was also essential to achieve proper development.

Flynn’s report also outlined how fish was transported and sold in Tasmania and the role of the municipal fish markets.

‘For some time past the fishing industry has received no help whatever from the Government. On the whole the conditions are such that, while the public complain of the high price of fish, the dealers state that the supply is inadequate, and the fishermen themselves as a rule say that the prices they

receive are not such as to afford them a decent living.’

He pointed out hat ‘almost all the edible fish in the Tasmanian seas are suitable for canning’ and several canneries had been established; but all had failed due to inadequate capital or lack of technical skill. Flynn’s analysis of the development question bears a similarity to both the 1882 Royal Commission and the Brendan O’Kelly’s 1997 report. The Fisheries Commissioner’s response was to

call for direct Government assistance to enforce its laws and stress the need for revenue for experimental work; but the more progressive of Flynn’s recommendations were ignored. Although all boats had been required to be licensed for many years no licence fees could be charged, the Commissioners requested the Government to reverse this situation.

Before the Royal Commission Report was tabled Walter Lee’s Liberals defeated the Earle Labor Government. Flynn’s report was debated in the House of Assembly in November 1916. The report

was not well received by the Liberals, the Premier said it was a waste of time and its recommendations were worthless. ‘He was very dissatisfied with the report … he read from the minutes of the report holding it up to ridicule … The whole thing was a ridiculous farce and he did not intend giving effect to any of the conclusions’. The former Premier, Captain J.W.Evans, criticized the selection of Flynn as Commissioner – ‘he was not the right man for the position’. Lyons and James Ogden mounted a defence based on the unacceptable price of fish – ‘a silver trumpeter to feed two people costs

two shillings and sixpence… The object of the inquiry was to try and find out whether the community could be served with cheaper fish’. They chided the Government ‘Was it the duty of the Government to look after the welfare of the people or to sit back and smile?… They were keen about a Mines and Agriculture Department then why not a Fisheries Department’.

Whilst the war continued Lee had little opportunity to review his decision, but lack of Government interest in the Report simply encouraged Flynn to resume his interest in other subjects. His academic research still centered on marsupials and this earned him a D.Sc. from the University of Sydney. When Errol was born the Flynns rented a large semi-detached villa, Mildura, in Warwick Street.

Later they lived in Darcy Street South Hobart. During her first pregnancy Marelle was avoided social contact but soon recovered her vivacity. She was beautiful, athletic, fun loving

and had theatrical ambitions, spoke both French and German, played the piano and loved dancing. Errol later said she was both religious and hypocritical—denouncing his wayward life but prepared to enjoy a somewhat bohemian life style when it suited her. Marelle was pregnant again in 1919 and late in the year went to Sydney to stay with her parents. Norah Rosemary Flynn was born

in Kirribilli on 2 December.

Flynn regularly travelled to England and on his visit in 1920 to conduct research at London University he was accompanied by the whole family. Errol, who had attended several schools in Hobart between 1917 and 1919 was sent as a boarder to South West College in London. Marelle and Rosemary settled in France and Errol remained unhappily at boarding school in London and Theo returned to Hobart alone..

Professor Flynn was alone and depressed. His personal turmoil spilled over into his work and he was criticised by the University for lack of attention to his classes, his accountsand ‘neglect of his income tax obligations’. After lectures he could sometimes be found at the nearby Heathorne’s Hotel. After his next annual visit he returned with Errol in tow and the pair moved into a house in the Glebe. Errol spent some time at Friends School and then a year at Hobart High School before being expelled. In desperation Flynn called on old acquaintances in Sydney to have his errant son enrolled as a boarder at North Shore Grammar School. With his estranged wife in France, Thomas Flynn devoted his life to the University and fisheries.

Flynn and th eTasmanian Labor Governments

When J.A. Lyons became Premier in October 1923 he and his Attorney-General, A.G. Ogilvie, set about reforming Tasmanian fisheries. Their first move was to appoint replacement members to the Fisheries Commissioners without the advice of the existing commissioners. Tom Murdoch, the influential MLC, was one of those appointed. The triumvirate of Ogilvie, Flynn and Murdoch moved to bring about fundamental change. Whereas Murdoch’s role was confined to the public sector Flynn was prepared to work in the private sector as well. Flynn’s reinvolvement in public affairs gave him a new lease of life. One of Lyon’s initial acts as Premier was to take up a theme from Flynn’s Royal Commission Report. He gathered together leading industrialists and formed the State Development

Board to promote economic development. A key member was Sir Herbert Gepp who had come to Hobart in 1914 as the first manager of the Electrolytic Zinc Company.. Flynn and Gepp had common interests and mutual acquaintances and worked closely together. Gepp, Lyons and Flynn shared a common understanding of the role of science in industrial development, and the responsibility of the State.

Flynn had already developed a proposal to utilise the untapped pelagic fish resource that had been described by Johnston in 1882. He convinced A.J. Nettlefold a Hobart businessman and alderman

on the viability of his proposal and the two put their case to Premier Lyons early in July 1924. Lyons was impressed and called an urgent meeting of the Hobart members of the Board to consider the proposal. Neither Herbert Gepp, Henry Jones nor Secretary Addison were present but Lyons discussed with J.H. Butters, C. Selby Wilson, Malcolm Kennedy and David Kennedy his idea of ‘catching, preserving and canning sardines’ and other pelagic fish at St. Helens. Dunalley was a thriving fishing port but there was no other significant fishing settlement between it and Victoria.

Flynn had pondered the question of why, if the availability of pelagic fish had been established so long ago, was there no industry exploiting them. He was not the first to do so and certainly not the last. His answer was that the absence of scientific information on the biology and behaviour of Tasmanian fish was the cause, thus he and Nettlefold sought from the State Development Board ‘the assistance of the government with a view to undertaking a scientific investigation in order to prove the most suitable months of the year for fishing, the habits of the sardines, the best methods of fishing forthem and other data at least desirable if not necessary.’ They estimated that capital of £150,000 would be needed for the venture – to build the factory, obtain vessels etc. and to tide the venture through

seasons when fish might not be available.

In addition to the lack of scientific information Flynn believed that British migrants were needed to bring skills not then available in Tasmania. ‘The lack of a hereditary fishing population’ he wrote in 1927 was also a major factor in inhibiting the development of Tasmanian fisheries. Thus Flynn told the Board that about 50 immigrant families would also be required.

The Board enlisted the Fisheries Commission and its Water Bailiff Tom Challenger to evaluate the project. A Committee comprising of Dr. G.F. Read (Chairman), Flynn and H.W. Knight (Secretary to

the Fisheries) was appointed in July 1924. The Commissioner of Police made available the services of Water Bailiff Challenger and a continuous investigation was carried out from September to November 1924. Whilst their report was being prepared Flynn discussed fish canning with the Tariff Board and reminded them that despite imports of over £1 million of fish a year, mostly canned, Australia had not a substantial fish cannery. The report of the Committee was submitted to the Board in April 1925 and included the following: during the last eight months, it (George Bay) is one vast quivering mass of darting shoals that seem to come and come and never end their coming. Indeed it is a revelation. Our investigations go to show that the fish come into the Bay about late August

or early September lasting for a least 8 months….Further we know that these fish also exist in huge shoals in the open sea outside the bay from which they pass in an apparently continuous stream

inwards.

The report convinced the State Development Board. Premier Lyons wrote to Professor Flynn, ‘if you can suggest any reasonable means by which this Government can further your enterprise,such suggestions will receive my favourable consideration.’ With this endorsement Tasmanian Fisheries Development Pty. Ltd., was registered on the 4th September1925 with a capital of £5000 – 100 shares at £50 each, 90 shares being takenup. The Directors being Flynn, F.C.Shaw, C.O.Chambers of Victoria and Jos.Nichols’. The Fisheries Commissioners supported the proposal and Government

concessions to the company. With his project approved Flynn urged the Development

Board to now investigate ‘the whole question of Tasmanian Fisheries.

Whilst the Board supported the project they urged that the first stage be confined to the production of fishmeal, fish oil and fish manure (a low-grade meal). Flynn contestedthe reservations

concerning canning, and it is interesting to compare this decision with the development of fish plants at Triabunna in 1974 and 1985.

A New State Fisheries Administration

Albert Ogilvie, the Attorney General in the second Lyons Labor government, took up another aspect of Flynn’s Royal Commission and discussed a new fisheries administration with Flynn and

Murdoch in October 1924. The management of fisheries was in turmoil for all the regulations were found to be invalid, as were all of the decisions taken by the Commissioners in the preceding 30 years.

The election of the Labor Government had revived the debate about the use of craypots. The Commissioner sinitiated another inquiry on the subject in May 1925 with Flynn as a member. The

Committee reported in June and the majority again found against the pots but Murdoch and Flynn submitted a minority report recommending that pots be legalised under certain conditions including prescribing the design of the pots. The recommendations in the minority report were almost identical to those ofLyons in 1913 and a 1916 report by Flynn.

The ineffective handling of the craypot question and the fiasco over the Regulations strengthened the resolve of Ogilvie and Lyons to legislate for the replacement of the Fisheries Commission with a new body and then legalise the craypot. Safely re-elected with an increased majority and recalcitrant Legislative Council mollified, Ogilvie instructedColonel Lord, the Police Commissioner and Flynn to consult with the Parliamentary Draftsman on a new Fisheries Bill.

Ogilvie introduced a Bill to completely overhaul fisheries administration and rewrite the Fisheries Act in October 1925. The Bill implemented many of the recommendations Flynn had made as Royal Commissioner. It left the Commissioners responsible for inland fisheries only. Another board composed of three members would control sea fisheries. The Sea Fisheries Board would be very small but not a department in its own right and would operate as an adjunct of the Police. Its chairman would be the Police Commissioner, its secretary the Secretary of the Police Department, and its rules would be implemented by Police Officers. Ogilvie announced that the boards would not cost the taxpayers anything. The Sea Fisheries Board could keep all its revenue for one year but then would have to pay half to the Treasury. Board members would be part-time and honorary but could receive £50 per annum from the revenue collected. The separation of inland and sea fisheries and the lay nature of both boards followed closely the English administrative model except that in England the members were elected and the jurisdiction covered smaller areas in the main.

In Parliament the Leader of the Opposition (McPhee) defended the status quo and questioned whether the change would do anything to develop the fishing industry but other members of his party

including the former Premier J.W.Evans supported the view that it was now time to separate freshwater and sea fisheries administration. Ogilvie admitted he had some doubt about the size of the Sea Fisheries Board and agreed to an amendment to increase it to five providing the Police Commissioner was still the Chairman. Ogilvie and Lyons had been forced to omit the legalisation of crayfish pots

from the Bill due to the opposition led by Robert Cosgrove. They decided to leave it to the new Board to make the decision but certainly appointed a Board that who would allow their wider use. Cosgrove attempted to forestall this strategy by moving an amendment to the Bill that would insert a clause prohibiting their use. McPhee supported him but they could only gather two other supporters and their amendment was lost. Somewhat surprisingly when the Bill reached the Legislative Council later in November there was no debate on craypots and no objection to the creation of the two boards; the prior agreement of the angling bodies certainly contributed to this. W.B.Propsting, who had proposed a similar arrangement someyears earlier understandably supported the Bill and with the aid of Tom Murdoch ensured that the measure passed smoothly.

Ogilvie’s original intention was that the three member Board should be Lord, Flynn and Murdoch. Flynn was to provide the development impetus and the scientific support. He was formally offered the position as soon as the Bill was passed and he immediately accepted but pointed out that ‘it had been suggested in some quarters’ thathe was ineligible due to section 5(4) of the Act which had been

inserted in the Legislative Council on the motion of C.J.Eady. The section forbade persons ‘beneficially interested in the sale of fish’ from being members of the Board in order to avoid conflicts of interest, of which Flynn himself had reported on in 1916.

Flynn was a Director of Tasmanian Fisheries Development but he argued that the object of the company ‘is only the development of prospects of an industry. It is not intended… to sell fish in any way.’ Nevertheless he suggested the question be placed before the Crown Solicitor. Flynn’s interpretation of what the company intended to do may have been correct but the Crown Solicitor found that the

Articles of Association of the company expressly declared that the objectives were to carry on fishing, fish canning and preserving for profit and thus the professor was ineligible. Ogilvie accepted the advice and Flynn was not invited to join theBoard. Flynn’s exclusion did not prevent Ogilvie’s law firm Okines and Ogilvie from being appointed solicitors to the Board. Subsequently he regularly

prosecuted illegal fishing cases on behalf of the Board until he became Premier in 1934. Flynn was appointed scientific adviser.

The Labour Government had provided whole-hearted support by legislating to give Flynn’s company exclusive rights to a substantial area of the east coast waters. Ogilvie had introduced the Fish Canning Encouragement Bill on 19 November 1925 by stressing that it gave concessions for fish for canning purposes only and did not create a monopoly. Other enterprises could be established on other parts of the coast and it ‘did not interfere with ordinary fishermen in any way’. The Bill received bipartisan support but in traditional fashion fishermen objected to any concessions to others and were able to stir up parliamentary opposition. On this occasion Messrs. Culley and Sheridan, with some support from Sir Walter Lee objected and pressed for a Select Committee to consider the Bill.

Ogilvie sought to save the Bill by conceding the removal of crayfish from the list of species the company would have exclusive rights to in the concession area. When the debate resumed the next day Ogilvie agreed to also remove barracouta from the list but Culley persisted pressing for the inquiry ‘to ascertain whether it was in the best interests of the fishing industry that the company should

set up operations’. The debate dragged on and finally Cabinet agreed to a Select Committee enquiry to be chaired by Robert Cosgrove.

The Committee heard evidence from Flynn, N.P. Johnson, who formerly operated a small cannery at St. Helens, Knight, Clive Lord and J.E.C. Lord from the Fisheries Commission and five fishermen.

Finally the project was approved on three conditions:

– the concession area was reduced by excluding the area between Cape Tourville and Schouten Island.

-the company was required to spend at least £35,000 of capital to retain their licence and was prevented from taking or selling fish for consumption in Tasmania as freshfish;

-the prospectus must be approved by the Minister.

The recommendation for changes was accepted and the Bill became law as The Fish Canning Encouragement Act1925.

The Bill passed, Flynn set off for London to raise the capital accompanied by another director R.G. Narelle ‘a prominent American businessman and President of Atlantic Lighterage Co. of New York.’ Lyons instructed the Agent-General to give all assistance to the partners but on the understanding that the Government was not associatedwith the flotation of the Company. Flynn was also commissioned by the new Sea Fisheries Board to bring back the latest advice on fisheries management. The first attempt to raise capital on the London market failed and Flynn returned to Hobart.

While Flynn was in Europe the new Sea Fisheries Board was holding its first meeting. Despite being asked to gather information abroad, and his position as scientific adviser, nine months passed and Flynn still had not been invited to attend a Board meeting. He wrote to the Chairmen privately questioning the action and was told that he was not a member of the Board and ‘he would be asked to attend when required’. In disgust he wrote to Ogilvie tendering his resignation. Flynn reported to the Minister that he had told Lord it is impossible to say in advance whether scientific advice would be required at any meeting. ‘I am sorry for this position because you know how hard I have worked to bring about the present Fisheries Laws and Government’.

Ogilvie was able to convince him to withdraw the resignation and to restore Flynn’s relationship with the Board that considered his proposals at the next meeting on the 27 September, but the incident revealed a fatal flaw in the structure of Board. None of the Board members had a scientific background and none any training in the management of fisheries or the behaviour of fish stocks under exploitation. They were no better equipped than their predecessor and perhaps less so, relying on the advice of Sgt Challenger. The Chairman had apparently no idea that the regulations they had worked so hard on, particularly the minimum size of crayfish was just the kind of subject on which scientific advice was vital.

Flynn outlined ‘a very ambitious program of research’ for the Board. He proposed a comprehensive study of the biology and ecology of both the oyster and crayfish and for ‘marine fish, times and places of breeding, development, recognition of larval forms etc.’ The Board’s response to the proposed program was to find that ‘it could not see its way to incur expenditure in undertaking so extensive a scientific investigation’ but would give further consideration to the oyster work. Despite this finding the Board had spent some time in July discussing what to do with its revenue and had decided to invest £600 in stocks redeemable in October 1928 and £400 in a fixed deposit, leaving £2250 in hand. His other proposals were also effectively ignored. When the Board offered him a salary of £25 –

half the amount they paid themselves and the Secretary. Flynn again felt affronted but Ogilvie kept him involved.

Flynn continued to be investigator, promoter and adviser; he reported on the biology of bream in November 1927 and was asked for his opinion on the availability of cuttlefish following an enquiry

from Argentina. He also met the British delegation of bankers reviewing theeconomy known as the ‘Big Four’ and provided them with a written statement.

Flynn and Gepp in developing national fisheries

While Lyons Ogilvie and Flynn strove to promote development in Tasmania the Commonwealth Government also began to take a serious interest in fisheries. The Tasmanian Government provided virtually no funds for the management or development of fisheries for the fifty years after 1890. After federation the State looked to the Commonwealth Government to finance fisheries development.

The loss of the Endeavour had quenched the Commonwealth’s early enthusiasm for fisheries development for many years until Herbert Gepp urged on by Flynn took on a national role. In 1916 Gepp was appointed to the Advisory Council of Science and Industry and remained an influential participant in the evolution of that body through the Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry to the Council for Science and Industrial Research. In 1926 he attended an Imperial Conference in London to give further consideration on how the British Government’s £1 million annually ‘to promote inter-Imperial trade’ should be used. Gepp was now chairman of the Development and Migration Commission established to facilitate the initiative and link Australian industryto an Empire marketing scheme The Conference proposed that fisheries development should be a part of the scheme and commissioned a Fish Report.

After the Conference Gepp accompanied Prime Minister Bruce to a meeting with the British Prime Minister, Lord Balfour, where they discussed the possibility of the Secretary of the British

Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, visiting Australia to promote further scientific co-operation.,

Sir Frank Heath visited Australia in 1925 and talked with Flynn and appears to have concurred with much of his fisheries development philosophy. Heath’s report was the basis for the establishment of CSIR and it included recommendations that the new organization undertake fisheries research in addition to its other activities. Heath proposed that Tasmania be the centre for national fisheries program.

A National Fisheries Research facility

Tasmania was not the only State to covet a fisheries research station and Flynn’s eminence on the national fisheries scene was not unchallenged. The acceptance of the Heath Report provided the Victorian Government with an opportunity to act on one of recommendations of their 1919 Royal Commission. The Premier of Victoria wrote to the Prime Minister urging the establishment of a ‘central marinebiological laboratory’; the request was referred to the Executive of the newly formed CSIR. The Executive deemed the matter to be an economic problem and therefore the province of the Development and Migration Commission; ‘later it (CSIR) might be prepared to conduct scientific research’ in fisheries. W.A.Haswell, Professor of Zoology at the University of Sydney, lobbied for the facility to be located in Sydney, as did the NSW Director of Fisheries D. G. Stead.

In March 1926 the Acting Director of the Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry, Gerald Lightfoot, prepared a confidential report on the consequences of the Heath Report. It largely concentrated on the establishment of a fisheries research station. He recommended that David Stead be invited to prepare a further report. Stead was highly critical of any suggestion that fisheries

research should be centred in Tasmania. It was obvious, he stated ‘that the fisheries station should be in such a position as will enable it to be used for the practical training of investigators

and scientific and commercial fisheries men generally.’ To Stead the coast of New South Wales was both the most highly developed

fisheries area and where current and potential development was centred.

‘It would therefore be highly unreasonable, unscientific and altogether an unpractical thing to construct such a station where the section of the people needing it most could not have access to it….If the first fisheries station to be established in Australia is set up in Tasmania and far removed from the centres of population and of observation, there is but little doubt that it will develop into the type of marine biological station in which economic work is scarcely considered at all….We have waited so long for the development of a fisheries station in Australia that we cannot afford to play with the question by establishing some institution in our ocean ‘backblocks’ so far removed from the ordinary scientific and commercial life of the community, as to be of littlepractical use.’

He concluded that Heath’s suggestion clearly indicated an absence of familiarity with the outstanding factors controlling the distribution of economic organisms in Australian waters and modestly

concluded ‘I am constrained to point out that I am the only Australian investigator who has dealt broadly in a private or public capacity with general scientific and economic fisheries investigations….Incidentally I may state that the only established great deep sea fisheries of Australia were made possible as a result of the preliminary investigation work carried out by myself.

Stead’s virulent criticism was echoed 50 years later when it was again mooted that the national fisheries and oceanographic laboratories be moved from Sydney to Hobart.

The Development and Migration Commission

The reluctance of CSIR to take an interest in fisheries left the field in the hands of Gepp and the DMC and so allowed Flynn to strongly influence national fisheries policy. After a survey the economy of Tasmania by the Commission, the CSIR and the State Development Board fisheries was listed as both a national and Tasmanian development priority.Interest was further enhanced by the response in England by Flynn’s venture.

When Gepp visited Tasmania in the first half of 1927, Flynn was again overseas promoting his project but on his return he presented a major submission to the Commission, entitled ‘Fisheries

Development in Tasmania’. His views were consistent with those expressed in the Fish Report; he stressed the high imports of fish and the dearth of an Australian fish processing industry. Australia needed and could sustain a fish meal industry. In his mind the lack of development was a consequence of the paucity of scientific knowledge and lack of a fishing population. Currently, due to the collapse of the Russian market for British herrings, skilled fishing labour could be encouraged to migrate to Australia. Flynn also referred to the suitability of Tasmania for fisheries, fisheries research and

fisheries education. He maintained that the research needed to support the development of fisheries should be coordinated with teaching and concentrated at one university, not duplicated throughout Australia.

In September 1927 Gepp hosted a major national conference on the development of Australian Fisheries immediately after the Fish Report became publicly available. The Sea Fisheries Board authorised the Chairman and Professor Flynn to represent them. The Victorian request and the urging of Flynn prompted Gepp to include the subject of the research station on the agenda. The highlights of Flynn’s earlier submission to the Commission were repeated almost word for word in the opening addresses by Senator MacLachlan and Gepp. The Conference ran for six days but found that the matters were such that seven sub-committees were needed to continue the work. Flynn and Lord were each elected to four of them.

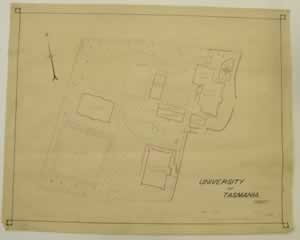

Flynn chaired the Sub-Committee to investigate the marine biological station, four of the six other members were also university professors (Nicholls (WA), Goddard (Qld) Agar (Melb) Harrison (Syd)), in contrast to the Conference itself where the academics were in a minority. Taking advantage of the ANZAAS Conference in Hobart the Sub Committee met there in January 1928 and not surprisingly reported that due to ‘the diversity of conditions and problems biological stations should be established at various points on the Australian and Tasmanian coasts’, the stations to be of equal status but not necessarily of equal size. They should be managed by the local Professor of Biology, the Museum Director, Director of Fisheries, and representatives of the State and Commonwealth Governments. There should also be a Marine Biological Council of Australia and a Federal Bureau of Fisheries.

Not dissuaded Gepp and Flynn proposed to the Premier Lyons that the State should share the costs (estimated to be £6000 capital and £1500 a year) with the Commonwealth. Lyons was reported to be ‘favourably disposed’ to the idea and agreed to discuss it in Cabinet. Plans were prepared for the Tasmanian station but whilst being considered the Lyons Government was defeated at the polls in May 1928. The plans are now in the Archives of the University of Tasmania. Flynn’s ambition to build a national fisheries research station in Tasmania were finally thwarted by CSIR. Professor Dakin (University of Sydney) approached the head of the organisation, David Rivett, in May 1929 with a proposal to establish the research station near Watson’s Bay, in Sydney Harbour, in collaboration

with the University of Sydney. Rivett was impressed and wrote to his colleague Arthur Richardson saying that we should ‘put it before the Fisheries Conference at its next meeting and try and carry the whole thing through, incidentally killing the previous unpractical and rather foolish schemes which have been or are floating around amongst the members of that rather heterogeneous assembly.’

In 1935 Dr Harold Thompson was appointed to head a CSIR Division of Fisheries and the national fisheries research program started. In 1970 it was transferredfrom its original site in Sydney to Hobart.

By early 1928 Flynn’s Company was still only a prospectus so an approach was made to the Development and Migration Commission for assistance. His proposal for the establishment of a fish canning

and fish preserving industry, including the possibility of securing skilled fishermen and operators from England and Scotland, was exactly the kind of activity the Commission wanted to promote. Following the first national Fisheries Conference Gepp asked F.L.McDougal to closely follow fisheries matters in Britain, these investigations confirmed Flynn’s view and revealed considerable interest amongst British fishing companies in establishing operations in Australia. One owner was prepared to bring his fleet of 14 trawlers and crews if the Government would guarantee duty-free entry, assisted passage for crews and families (700 people) and some ‘further aid from private capital or Government’. Gepp lent his support to Flynn’s scheme but the defeat of the Lyons Government

and the economic depression spelt trouble. Although the new conservative Lee Government, somewhat reluctantly, extended the period of the concession the required capital remained out of reach.

By 1929 Gepp’s Commission had been in operation for three years when he chaired the second session of the Australian Fisheries Conference in Sydney in July. Considerable progress had been made in overcoming the lack of information that the first session in 1927 blamed for the lack of fisheries development. The sub-committees established in 1927 had reported. Flynn worked diligently for the Conference writing both the Biological Station Committee and Preserved Fish Committee reports and with Roughley the Oyster Report. He was againan important figure in the deliberations of the Conference that again centred on the low level of fish consumption in Australia and the high level of imports.

The Conference resolved that in order to utilise the nation’s fish resources the Federal Government should immediately set up an organization with equipment to conduct scientific, statistical and practical investigations of commercial and potentially commercial fisheries. The U.S. Bureau of Fisheries was recommended as a model for the proposed Australian national organization. The proposed ‘Australian Bureau of Fisheries’ should have an ‘investigation trawler’ to continue the work of the Endeavour and a competent man appointed Director ofFisheries. Flynnmay well have seen himself in this position.

All too late

The defeat of the Bruce-Page Government in November 1929 signalled the end for the Development and Migration Commission and the power of Herbert Gepp. As Gepp’s influence waned Joseph Lyons’ career reached new heights. After his defeat in Tasmania in 1928 he had moved into federal politics. In 1929 he was acting Treasurer in the new Scullin Labour Government. Two years later he abandoned the Labor Party to join the UAP. In 1932 he became Prime Minister and in October 1933 committed theCommonwealth Government to a program of fisheries research. He pledged a sum

of £20,000 to procure a vessel specially designed for exploratory work on pelagic fisheries. In addition experiments on fish canning and the testing of other methods of preserving fish would be carried out. The Commonwealth would also cooperate with the States in a study of the distribution of fish products.

Unfortunately T.T.Flynn did not hear his former friend’s backing for an idea he had proposed seventeen years earlier. In addition to his national responsibilities Flynn had continued to advise the Tasmanian Fisheries Board until 1930. He sent them the results of his research and reported on fecundity of crayfish and commented on the Roughley report on oysters until the Ralston Trustees ‘for some reason’ asked him to ‘discontinue work on fisheries and to concentrate on other aspects of the research program’. Realations between the University and the ralston Trustees had been deteiorating for some time due to the Universities failure to actively seek complementary funding and finally they decided cut the funding for Flynn’s position from the level of professor to lecturer.

Not prepared to accept these changes Flynn returned to Sydney and wrote to his his former teacher J.P.Hill in September 1930. They decided he should take a year’s leave and come to London

to seek another position. The Rockefeller Foundation awarded him a grant in January 1931 to conduct marsupial research with Hill. In June of that year he left Australia to take up thechair of Biology at Queens University Belfast. He was able to continue his marsupial research and later return to his marine research as founding director of the University’s marine research station at Portaferry. Flynn was a fellow of the Linnean and Zoological Societies of London and the International Institute of Embryology and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. For his work as Casualty Clearing Officer during the War he was awarded the MBE in 1945.

Flynn spent twenty years in Ireland. Marelle and Rosemary spent most of this period with him but Errol made a life for himself at first adventuring in New Guinea and then in films. He

became an international star living in America and later in Jamacia. He married three times and had four children.

In 1947 Rosemary married Charles Warner a staff officer in the United States Air Force. Theo Flynn retired in 1948 and went to Jamaica to manage Errol’s Estate near Port Antonio. Theo bothenjoyed sailing on Errol’s yacht Zaca but Marelle was never comfortable too far away from London and Paris. She would regularly return to Europe from Jamaica when Rosemary lived in Germany. Most ofher family suffered with heart disease and Marelle had a heart attack in 1950. She rebuilt relationship with her family and spent Christmas with her sister in Florida in 1950. She was aninveterate traveller particularly enjoying driving herself through Europe and in 1951 her motoring resulted in a serious accident and Charles Warnerlaidon the resources of the Air Force to fly his mother-in-law to

hospital.

From. Frederick A. Aldrich comes an account of one of Theo’s early cruises with Errol. ‘the father was invited to join his son on a cruise to the seas off Mexico and Guadalupe

to “study marine life”. T. L.T. Flynn accepted and, along with the much respected, yet controversial American ichthyologist, Dr. Carl Hubbs, the planned cruise, sorry, expedition, got underway. Hubbs was from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at La Jolla, California. (Incidentally, one ofhis former graduate students and a member ofthe staff of the Academy wasresponsible for the identification of the fishes from our Amazon efforts). Complete with nets, dredges, seines, submarine lamps, traps, water glasses and aquaria, the Zacca, Errol Flynn’s 118-foot schooner, set sail in August 1946.

The crew was probably unique. There was Jerry Courneya, to film the expedition. A drinking buddyof Flynn’s, John Decker, was “signed on” as artist, as Higham puts it, “to paint marine specimens”. A poor choice, I’d say. Decker was reputed to be a “way-out” painter whose work adorned the walls of restaurants frequented by Flynn’s pre-jet days jet set. One such painting of Decker’s is a portrait

of Queen Victoria, the head being one with the features of W. C. Fields. Then, there was Nora, Flynn’s second wife, “great with child”. Also present was the archer, Howard Hill, whose skills with the bow and arrow thrilled me in Flynn’s movie “The Adventures of Robin Hood”, when I was in my teens. All the time I thought it was Robin of Locksley’s arrow that split the shaft of his opponent’s arrow in the target at Basil Rathbone’s “archery contest“!

As they got underway, Professor Flynn must have looked out to sea from beneath his red, bushy eyebrows, with the sense of excitement he had had so many years before whenhe was biologist on the cruise of the Aurora to the South Pole. But this cruise was different. There was booze and drugs, a near miscarriage, and precious little science. The seas were rough, and both Nora Flynn and Decker

suffered badly from seasickness. So badly, in fact, that they – and what amounted to a mutinous crew – left the Zacca at Acapulco, Mexico. But some “science” there was. Hubbs made observations that figured largely in his major publication on the behaviour of flying fishes. Among the San Benito Island s they observed the behaviour of sea lions, seals and sea elephants. No fewer than fifty new or unusual species of fish were taken.

T. L. T. Flynn was in the custom of assigning patronymic names to new taxa he described. He continued his custom and three new herrings of the genus Gibbonsia he named G. errolae (for his son), G. norae (for his daughter-in-law) and, in honour of theschooner, G. zacae. Yes, it was quite a trip.

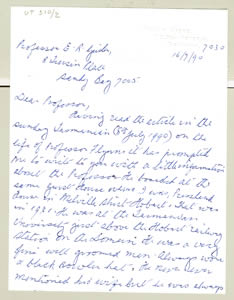

Whilst in Jamacia Theo involved himself with civic affairs including sitting on the bench as a JP. But he remained interested in research and made enquiries about some link with an American university. Marelle never fully accepted Errol’s life style and was anxious to return to England. In 1954 J P Hill ‘Theo’s teacher, research collaborator and best friend’, died in London. Theo and Marelle hurriedly flew back to arrange his papers and lodge them in appropriate libraries. Prompted by Hill’s daughter Theo arranged another Rockfeller Grant to allow him to spend two years in London finishing some of her father’s papers.

T T Flynn suffered a mild stroke in 1959. He and Mareele had left Jamacia the previous year and Errol was most concerned for in the eight years they had spent in Jamacia the two had

become very close. Errol died later in the same year and the grieving parents moved to Italy for an extended holiday. Theo liked the climate and the life and so they sold their house in St. Albans, Hertfordshire and a bought a penthouse in Vermimiglia overlooking the sea. However the elevator was tempremental and climbing the stairs to the seventh floor was too much for two peolple nearly

seventy years old one with a bad heart and the other having had a stroke. Charles Warner had returned to the Pentagon and Rosemary settled back into life in Washington. So Theo and Marelle returned to England. Around 1961 they moved to Woodingdean, near Brighton in Sussex. Marelle died there in january 1968 after being hit by a car outside her home some weeks earlier. Theo went to stay

with Rosemary and Charles for a year and a half and then moved to a nursing home at Liss, Hampshire where he died aged eighty-five on 23 October 1968.

— Tina