The reviews are OVER THE TOP; here’s one:

— Karl

It is not too late to help Rory Flynn and Mike Luering, and Tours of Duty to go search for Sean Flynn!

Tours of Duty is preparing to return to Cambodia to continue the search for Sean Flynn and the journalists who disappeared more than 55 years ago. The mission is moving forward with optimism—and support right now will directly strengthen what the team can achieve on the ground.

This is a moment for those who believe in truth, history, and bringing closure to families still waiting.

Join the effort. Share, donate, and help carry this mission of hope forward.

Sean Flynn didn’t just report the war.

He fought in it.

In Cambodia in 1970, Sean Flynn — a photojournalist and the son of Errol Flynn — was credited by U.S. Special Forces with fighting alongside Green Berets during combat operations.

In one documented incident, Sean is widely credited with helping save an Australian platoon under fire, standing his ground when others could have fled.

He was not embedded for comfort.

He was there because people were dying — and he refused to turn away.

Weeks later, Sean Flynn disappeared.

He was never seen again.

⏳ WHY THIS SEARCH CANNOT WAIT

For more than 50 years, intelligence fragments, witness accounts, and field reports have pointed to specific locations in Cambodia where Sean Flynn may have been held or killed.

But Cambodia is changing rapidly:

Jungle terrain is being cleared

Development is erasing historic sites

Witnesses who knew the truth are aging or gone

If these locations are not searched now, the opportunity may be lost forever.

This mission represents one of the last viable chances to search for Sean Flynn using modern forensic technology.

THE MISSION

Tours of Duty is deploying a veteran-led recovery team to Cambodia to investigate long-standing leads tied directly to Sean Flynn’s disappearance.

This mission includes:

️ Drone and LiDAR surveys of high-probability locations

Ground verification of sites tied to witness testimony

Local interviews conducted before knowledge disappears

Field logistics that allow teams to stay long enough to work thoroughly

These tools did not exist when Sean vanished.

They exist now.

WHY SEAN FLYNN DESERVES TO BE FOUND

Sean Flynn was a son.

A brother.

A journalist who refused to be a bystander.

He stood with soldiers under fire — and then disappeared without a grave, without confirmation, without answers.

His family has lived with that silence for more than half a century.

This mission is not about fame.

It is about honor.

Sean Flynn fought for others.

Now we fight for him.

This mission may be our last real chance to bring him home — to replace rumor with truth and silence with answers.

If you believe courage deserves remembrance,

If you believe families deserve closure,

If you believe heroes should not vanish into history —

Help fund the search for Sean Flynn.

Help bring him home.

Some people document history.

Some people change it.

Sean Flynn did both.

We are going back for him.

— David DeWitt

The mission is accelerating as Tours of Duty and Mike Luehring prepare to return to Cambodia. Every hour matters. Conditions in the area tied to my brother Sean’s disappearance are changing, and without swift action, we could lose access to ground that may finally hold answers.

Moments like this don’t wait.

Access shifts, people move on, and critical information can vanish. Tours of Duty is ready—but reaching the field requires immediate support for travel, local teams, and equipment.

Please donate today. Stand with us. Be part of this mission—and help bring us closer to bringing Sean home.

— Rory

PLEASE put “For Rory” or “For Mike Luehring” in your donation so they can track donations!

The team leaves in a matter of weeks. They’re loaded, ready — yet we still need $4,450 to feed them.

$25 = one veterans’ meals for a full day of searching.

These aren’t paid guides or tourists. They’re veterans and Gold Star Family members returning to the jungles of Southeast Asia — not to fight, but to find those who never made it home.

Every mile they walk, every drone flight they launch, every unsearched crash site risks being lost forever: witness memories fade, jungle canopy reclaims the ground.

For just $25, you can provide a full day of meals for a veteran actively searching for our missing.

Why This Matters:

• $25 = one veteran fed for one day

• $100 = drone flights over a search grid

• $500 = mission-critical recovery tools

Your gift now makes it possible for them to go and stay until the job is done.

When you give, you are there in the field with them, providing the fuel they need to continue the search for our 81,000 missing servicemembers.

You are not just buying a meal. You are helping keep America’s promise: no one left behind.

Buy a meal. Fuel the mission. Bring them home.

Funds raised for a specific mission will support that mission whenever possible; remaining funds may be used to advance Tours of Duty’s overall POW/MIA recovery mission.

Journalist. Warrior. Hero. Still missing.

PLEASE put “For Rory” or “For Mike Luehring” in your donation so they can track donations!

Rory Flynn and Mike Luehring

Sean Flynn

Sean Flynn Candid

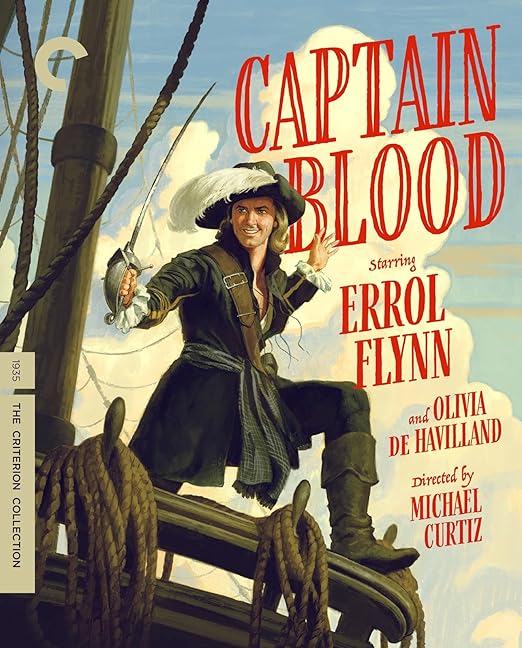

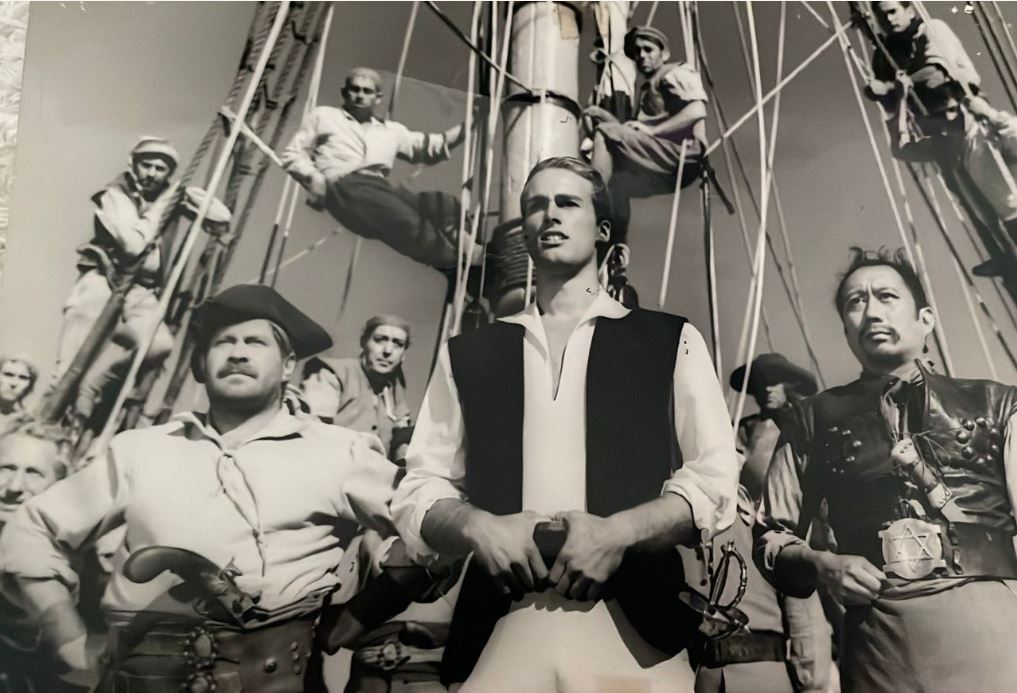

Sean Flynn in Son of Captain Blood

Sean Flynn with his mother film star Lili Damita

Tours of Duty Volunteers

Searching for the Missing

— David DeWitt