Per corollary of the ‘Objective Burma’ controversy, it is sometimes alleged that Errol harboured anti-British sentiments and vice versa. In fact, he was an ardent admirer of Churchill, and, as we know, the King and Queen.

This erroneous impression arose from two things, neither of which were Errol’s fault. The first was press speculation as to why he did not join up when Britain declared war on Germany (he was, after all, Tasmanian), and a few years later, why he did not join up when the US entered the war.

I am afraid that ‘anti-Errol’ prejudice was fuelled by his former friend, colleague and housemate, David Niven.

Niven came from a military background and had been educated at Stowe House (England’s first ‘progressive’ boarding school, but not quite progressive enough for the young Niv ,who was as sexually precocious as Errol).

After leaving Stowe he joined a Scottish regiment, before deciding on a career in acting. In Hollywood, however, he remained very ‘British’ and never took out US citizenship.

Deeply patriotic, when Britain declared war on Germany, Niven returned to England at once to take up his commission. He also let it be known, in private, that he believed ‘others in Hollywood’ – it was easy to guess to whom he referred – were guilty of dereliction of duty. Errol was Australian and in those days, when Australia was still part of the Empire, it counted as being British.

Lieutenant-Colonel Niven with his first wife, Primula Rollo.

Later, after Errol’s death, the usually affable Niven returned to the subject in his rather brilliant memoir of Hollywood, ‘Bring on The Empty Horses.’ .

This was the sequel to the bestselling ‘The Moon’s A Balloon’ , which vies with Errol’s ‘My Wicked, Wicked Ways’ as the best autobiography by an actor. I will stick my neck out here and say that Niven, stylistically, was a better writer – though less profound. I am judging this not on ‘My Wicked, Wicked Ways’, as we don’t know how much was written by Errol and how much by Earl Conrad, but on ‘Beam Ends.’

Niven devoted a whole chapter to Errol. Most of it is affectionate, yet because of this one incident when Errol seemingly ‘chose not to fight for his country’, there is a sour note and the general reader not versed in Flynnography would have had the impression that the lovable, good-eggish Niven regarded Errol as as a highly amusing 18-carat shit.

Sadly, very few people in the US , and probably no-one in the UK at that time, were aware of how desperate Flynn had been to enlist. Had Niven known the truth, he would have behaved quite differently.

But it is indubitably true that the controversy surrounding Errol’s ‘war record’, had not been helped by ‘Objective Burma’.

The film, as we have noted, had Winston Churchill and other senior politicians, as well as the British press and public foaming a la bouche.

It matters not one hill of beans if politicians or newspaper editors are upset. It is part of their job. Ordinarily, little upset Churchill – at least not in public. But what got under his skin – and he was a quarter American himself – was the very real anguish felt by British soldiers and the families of British war dead.

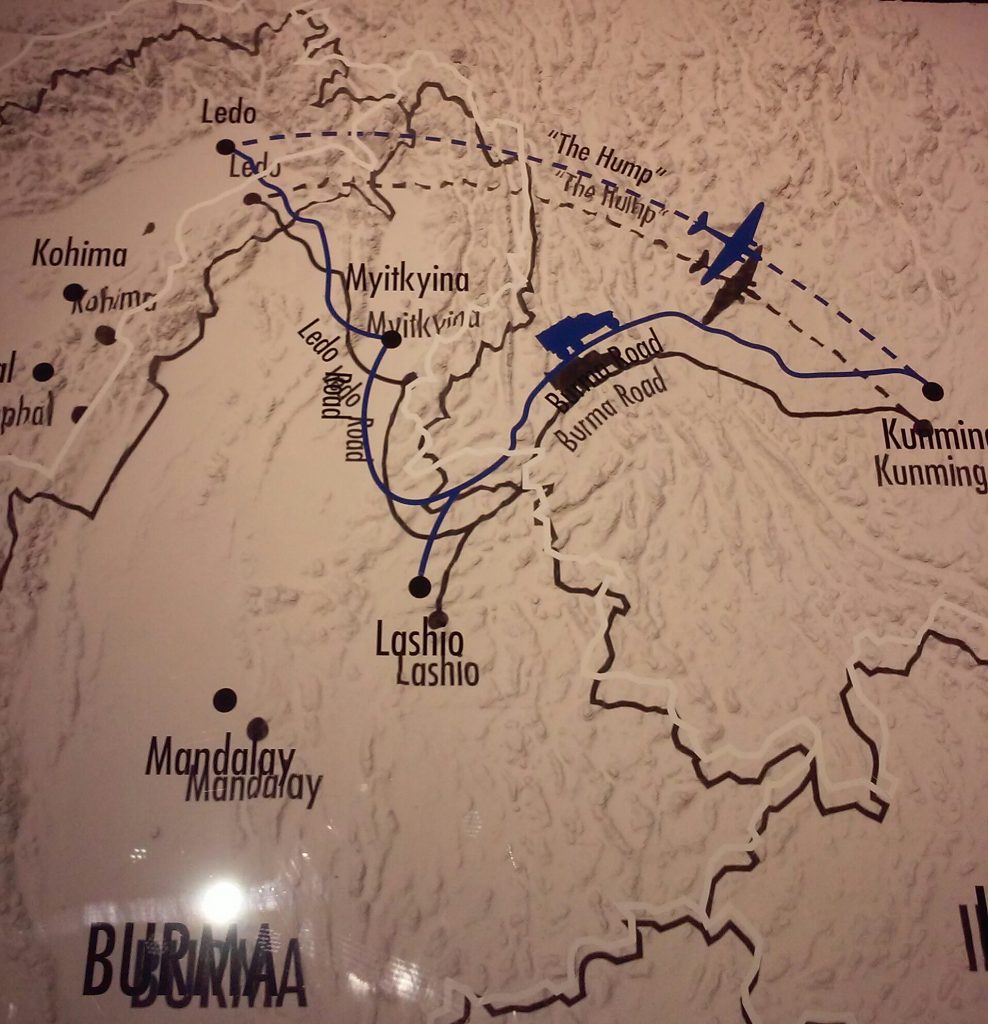

It has been asserted again and again, by both British and US military historians, that Burma was a British and Australian theatre of war, not an American one, and that the British incurred heavy losses there. The majority of Allied forces in Burma were British, South African, Australian, Indian and Chinese. The film caused offence not only in Britain, but in Singapore. Nor did it go down well with the Australians.

But the film was not banned in Britain and Singapore, as I originally and mistakenly suggested. Warner Bros pulled it from release in the UK after one week, horrified and dismayed by the offence it caused. The film was re-released in Britain in 1952, but only with a grovelling disclaimer.

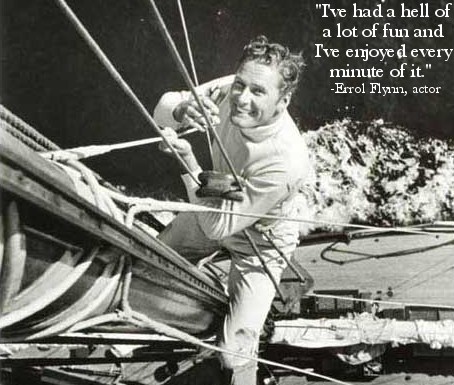

Of course the British press was quite wrong to take its ire out on Errol. All blame lay with Warner Bros, but it is always more profitable to be iconoclastic – especially when the icon to be toppled had made his career out of portraying action heroes in the cinema. Errol was an easy target, already notorious in his personal life, and a ‘shirker’ to boot.

A leading English newspaper printed a cartoon with the line: ‘Excuse me, Mr Flynn, but you are treading on some graves.’ From what I have heard and read, Errol was very distressed by this, and as a result, turned a bit sour on ‘Objective Burma’ (though he did regard it as one of his best dramatic performances), but was, of course, unable to defend himself.

Over ‘ere, Errol was ‘rehabilitated’ a long time ago. He is also taken very seriously as an actor. The Guardian newspaper recently ran a piece praising Errol as a man, a writer and an actor, and six months ago there was an Errol Flynn season on the BBC with commentary by some very distinguished people.

Christopher Lee, shortly before he died, narrated a very good documentary on Errol, commissioned by British television, which set the record straight and shows Flynn in an almost shining light. In fact, Flynn has never been so ‘In’.

And how can Brits not love him? No other film star personified English ‘chivalry’ the way Errol did, not to mention what is called ‘English Exceptionalism.’

‘Objective Burma’, however, cannot be rehabilitated as a ‘factually based’ film on any level, and was, to put it mildly, a little impolite to America’s Allies.

The Guardian, which is a left-leaning broadsheet, and if anything, tends to mock or denigrate British military achievements, wrote the most balanced, recent article on the subject of the film. Yes, it was a great war movie, but it was horribly insensitive and should not have been released so quickly, when British wives, mothers, and children were mourning the loss of their men.

(An interesting note. Lester Cole, who co-wrote the script, became notorious himself a few years later when HUAC accused him of ‘Un-Americanism’, and he became one of black-listed ‘Unfriendly Ten.’ Perhaps ‘Objective Burma’ was jinxed?)

Here is a link to the article

www.theguardian.com…

— PW