— David DeWitt

Archive for the ‘Main Page’ Category

Cuba Story Cover

Cuban Story – 1958, the Intro and Outro with Errol.

Just prepared and uploaded a video which is the clipped intro and outro of Cuban Story.

It's in the Blog Videos, here.

Russ

— Russ McClay

Steve Hayes – Googies Coffee Shop to the Stars Review!

Life & Style : Books

By Tommy Garrett on Oct 26, 2008 – 6:32:57 PM

Googie’s was a Hollywood hotspot that seemed to disappear, but for film fans and movie buffs, don’t despair. There is an excellent, well written and researched couple of books about the famed locale that leaves nothing to the imagination. The author is Steve Hayes. For those of you who don’t know him, but should, the British-born man explains that he first arrived in Hollywood in 1949 and moved there permanently in 1950. He was an actor for a decade or so, and he helped support himself by parking cars at Hollywood’s glamorous Sunset Strip nightspots as well as managing Googie’s, a coffee shop next to Schwab’s.

During which time, the author befriended stars like Errol Flynn, Tyrone Power, Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardner, Lana Turner and Robert Middleton. He says that they all influenced his life and gave him material for his autobiography. The author has also written movies and television.

Volume One starts out with the foreword by the legendary John Saxon, who was as famous for his looks as his acting skills. Chapters one and two are lead ups to some of the most fascinating stories of any book I have read in months. I thoroughly enjoyed his first meeting with the horror icon Bela Lugosi. Mr. Lugosi by this time was becoming an older man and had been typecast as a scary character in his movies. But it was also the author’s opinion of Jayne Mansfield that impressed me most about his knowledge. Jayne has been a bombshell, a sex symbol, but few people, other than those close around her, realized that she was actually very smart and a very loyal person. She did, however, as the author points out, never met a camera she didn’t like. I like his quote from Jayne, in which she uttered, “I wish I had been born thirty years earlier, because the movie stars of the twenties and thirties wore exotic costumes like Theda Bara and Gloria Swanson and Pola Negri. They lived in luxurious mansions, walked around with leopards on leashes, threw wild extravagant parties that lasted for days and were treated like Cleopatra. Oh my God, Steve, how incredible that must have been!”

Both volumes are filled with incredible stories by the author explaining his incredible interactions with some of Hollywood’s '50s and '60s royalty. That although the stars of that era thought the previous era icons were elegant and beautiful and fun. Today we long for the era that Hayes describes in such organic and yet exciting details. The author’s book is planned out in small chapters, each filling your mind and your heart with the love and admiration of yesteryear.

Though this author speaks wildly and with admiration of Hemingway, I find myself feeling the same way reading his books. Hayes is extremely talented and like Hemingway, he has a style that is forthright and yet leaves a lot to your own imagination. Though this book is thoroughly researched, it isn’t opinionated and the author had no axe to grind with any of the subjects. This is rare in today’s writing.

“Googies, Coffeeshop to the Stars” is a must-read for anyone who has ever wondered what movie stars and icons are like when they don’t think anyone is around to tell on them. Yet Steve Hayes does so with respect.

Googie’s is a Bear Manor Media publication.

— David DeWitt

David Niven on Merv Griffin – Higham Reference

David Niven on Merv Griffin circ 1981 with a Charles Higham reference… Robert Blake is a pain without knowing that Niv is terminally ill…

Check out Related Videos for Orson Welles and others…

Tip of the hat to our Author Bob Peckinpaugh…

— David DeWitt

Posted a Few Photos In Candid

Did some photo searching over the weekend and found some I haven't seen before. Uploaded to Candids.

Oddly the first photo in the album is one of them. The rest are at the end of the album.

Russ

— Russ McClay

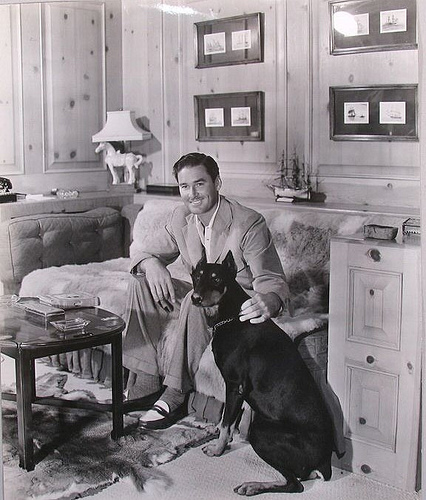

Happy days and nights at home…

Wish I coud see what those pictures on the wall contain a lot closer – looks to be ships! What a surprise… huh?

— David DeWitt

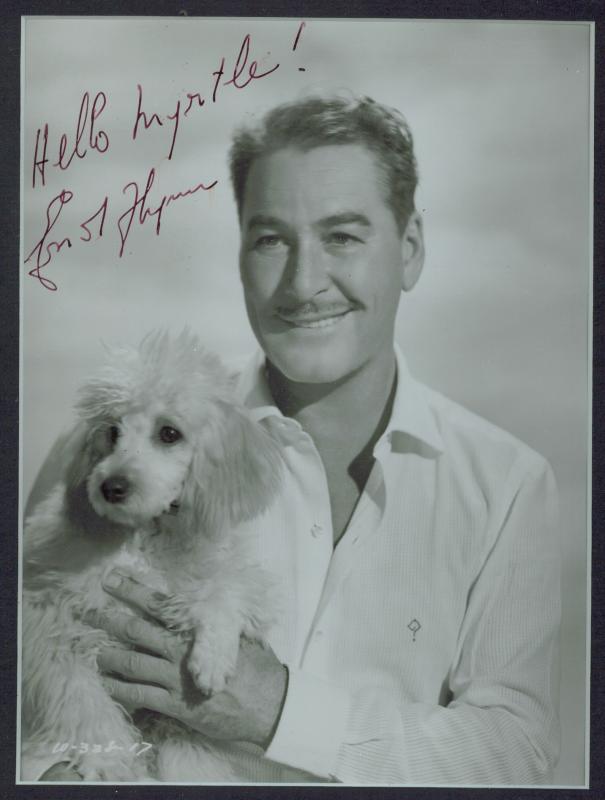

The Ramblin' Man Himself…

…left us on this day, October 14, 1959. He would have been 99 years old if he had not felt other winds blowing in a new direction…

…in Remembrance…

— David DeWitt