GREAT AMERICAN TRIALS

The Trial of Errol Flynn

January 11-February 6, 1943

Defendant: Errol Flynn

Crime Charged: Statutory Rape

Chief Defense Lawyers: Jerry Geisler and Robert Neeb

Chief Prosecutors: Thomas W. Cochran and John Hopkins

Judge: Leslie E. Still

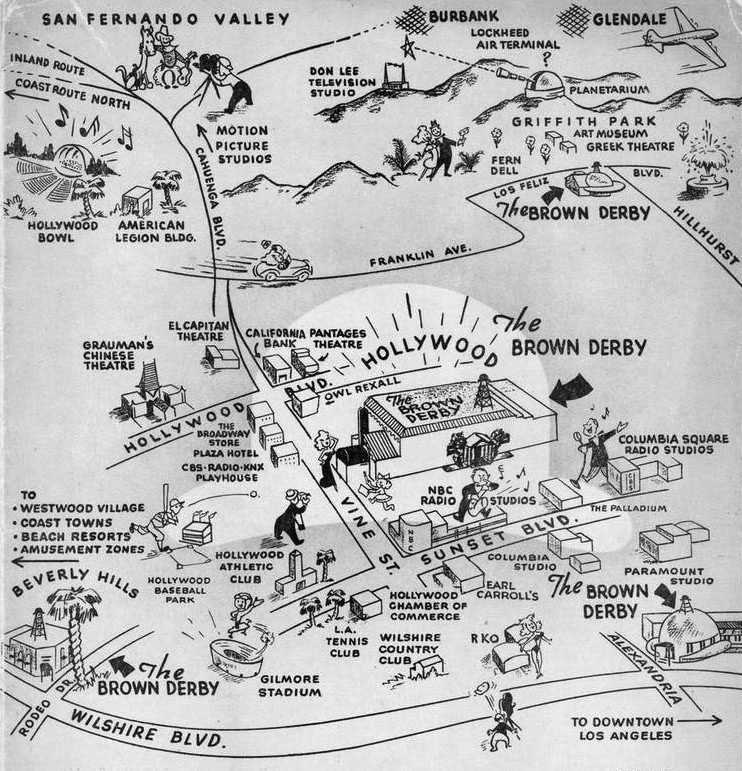

Place: Los Angeles, California

Verdict: NOT GUILTY

Significance:

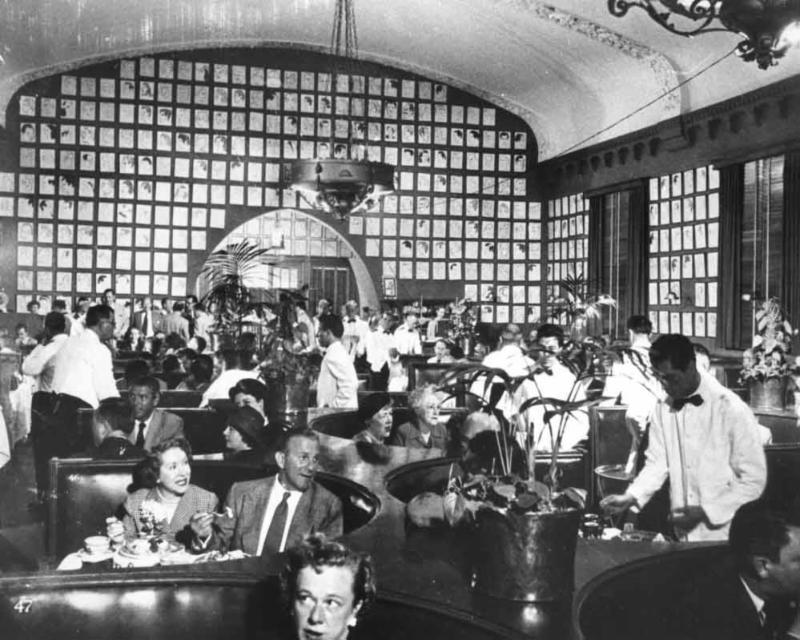

Despite the outcome, the Errol Flynn trial focused national attention on Hollywood’s sexual mores, which both titillated and shocked many Americans. The trial also put the phrase “In like Flynn” into the American language.

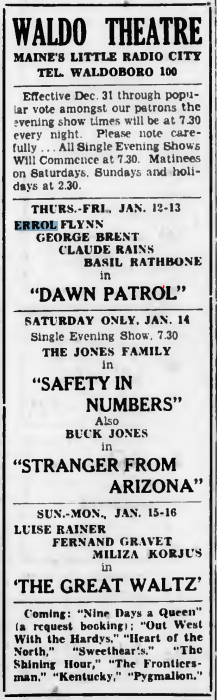

In 1942, Errol Flynn was at the height of his swashbuckling Hollywood career. In 10 years, the handsome native of Australia had made 26 movies—among them such overnight classics as Captain Blood, The Adventures of Robin Hood, and The Sea Hawk. Flynn lived a boisterous, daring life that was also devil-may-care. He worked hard, drank hard, loved hard. Women everywhere had fallen for his splendid physique, his cleft chin, and his enticing dimples, and women everywhere were available to him.

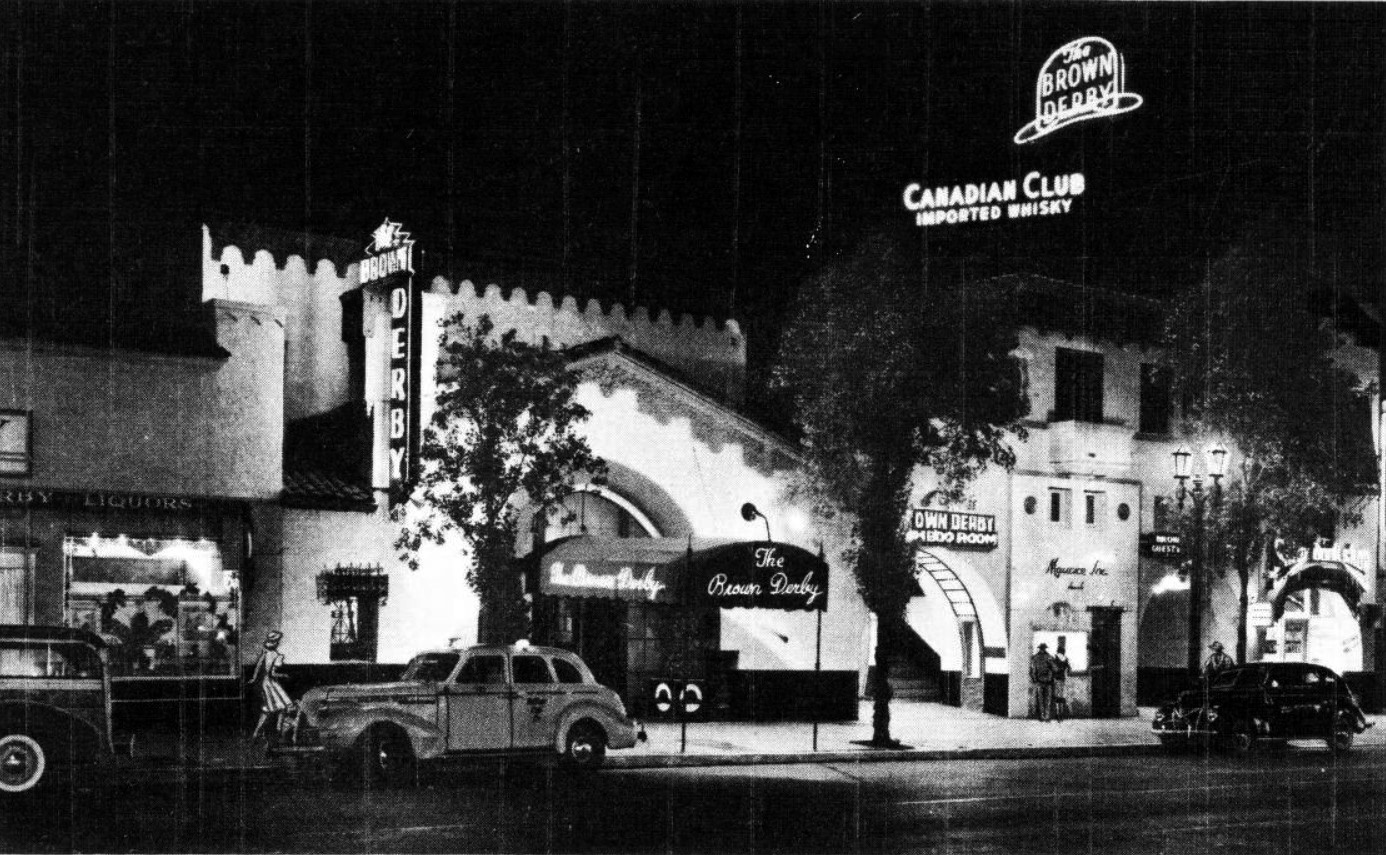

At a party in September 1942, Flynn met 17-year-old Betty Hansen, who arrived with a studio messenger and who dreamed of moviedom fame and fortune. By dinnertime, Hansen had thrown up from too much drinking.

The next day, Hansen told her sister that Flynn had taken her upstairs to clean up, then seduced her in a bedroom. A complaint was filed with District Attorney Thomas W. Cochran, who recalled a similar complaint by one Peggy Satterlee after a voyage aboard Flynn’s yacht. That charge had been dropped.

Flynn’s stand-in stuntman, Buster Wiles, later said Satterlee’s father had earlier approached Flynn with a demand for money, or, said Wiles, “he would lie to the police that his underage daughter had sexual relations with Flynn.”

Flynn was arrested in October. He hired Hollywood’s ace lawyer, Jerry Geisler.

Fans and sensation seekers thronged Flynn’s neighborhood, spying through binoculars, prowling over his 11-acre property, mobbing the courthouse at his preliminary hearing, pulling at his buttons and shoes.

Selecting the jury on January 11, 1943, Geisler purposely took nine women, gambling that the females’ attraction to the movie star would outweigh concern over the seduction of innocence.

Prosecutor Cochran opened with the Betty Hansen charge. Geisler’s cross-examination proved that her testimony was confused and that she was currently awaiting action on a possible felony charge with her boyfriend, the studio messenger.

“J.B.” and “S.Q.Q.”

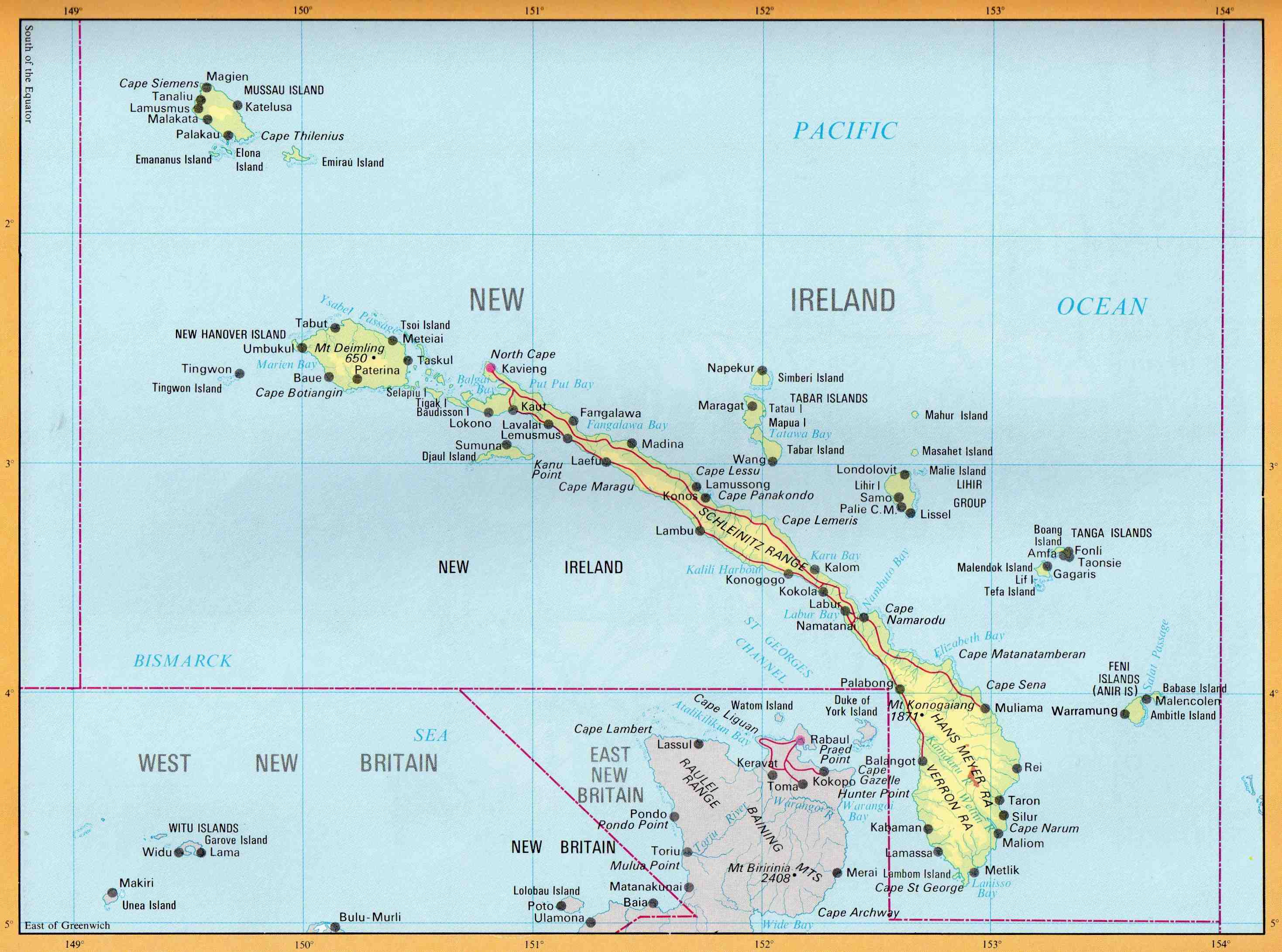

Now Cochran had Peggy Satterlee describe her voyage to Catalina. She said Flynn called her “J.B.” (short for “jail bait”) and “S.Q.Q.” (short for “San Quentin quail”)—evidence that he knew she was a juvenile. Nevertheless, she testified, he came to her cabin and “got into bed with me and completed an act of sexual intercourse”—an act against which, she admitted, she did not struggle. The next night, she said, he took her to his cabin to look at the moon through the porthole and there repeated the offense. This time, she said, she fought.

In cross-examination, Satterlee admitted to lying frequently about her age, then revealed that she had had extramarital relations with another man before the Flynn episode, and had undergone an abortion.

Taking the stand, Flynn denied the “jail bait” and “San Quentin quail” allegations, as well as entering Satterlee’s cabin or taking her to his cabin or taking Betty Hansen upstairs after she threw up at the party or having sexual intercourse with either girl. As he finished, women were crying hysterically. Men were yelling obscenities. The bailiff had to quell a near riot.

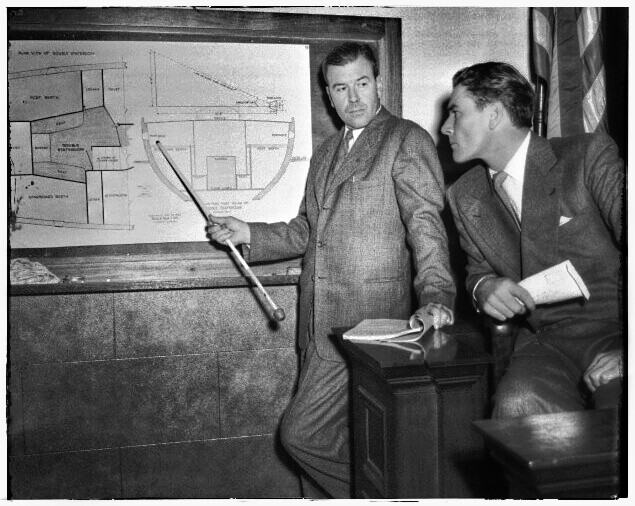

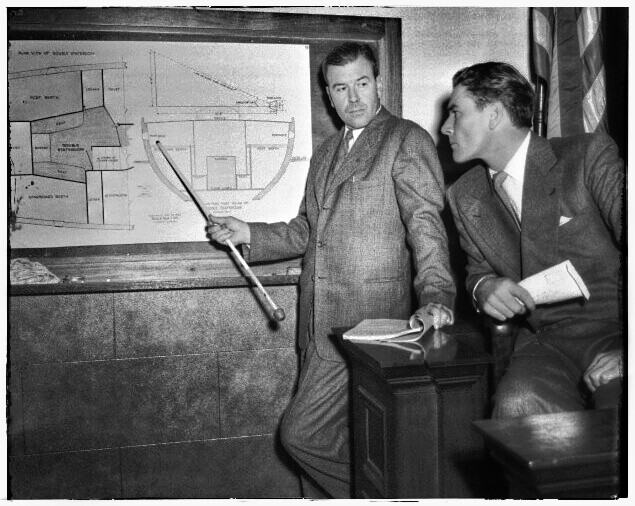

The prosecution introduced an astronomer to back up Peggy Satterlee’s description of the moon through the porthole. Geisler made him admit that, judging by the boat’s course, the moon could not have been seen from Flynn’s cabin.

The jury argued until the next day and found Errol Flynn not guilty. Said foreman Ruby Anderson afterward:

We felt there had been other men in the girls’ lives. Frankly, the cards were on the table and we couldn’t believe the girls’ stories.

Errol Flynn’s career continued, totaling some 60 films before he died in 1959.

—Bernard Ryan, Jr.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Conrad, Earl. Errol Flynn: A Memoir. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1978.

Flynn, Errol. My Wicked, Wicked Ways. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1959.

Thomas, Tony. Errol Flynn: The Spy Who Never Was. New York: Citadel Press, 1990.

Wiles, Buster with William Donati. My Days with Errol Flynn. Santa Monica, Calif.: Roundtable Publishing, 1988.

— Tim