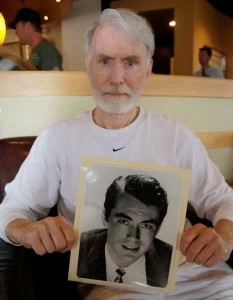

Today is my dear friend Steve Hayes 93, Birthday. Happy Birthday old boy!! Steve, was born Ivan Hurbert Hayes he was born on January 31, 1931, in Streatham, England, UK.

He came out of England to be an actor and he got a contract deal on 20th Century Fox. He had a speaking role in Botany Bay with Alan Ladd and James Mason.

The day he arrived he met a girl named Gloria and she took him up to Errol Flynn’s home in 1949. Both Flynn and Steve were British nationals and Steve had no place to stay. Errol invited him to stay with him at Mulholland Farm. In the two months that he lived with Errol, he stayed in the bedroom that Jack Barrymore stayed in. The room was painted a mustard yellow and it had the famous balcony that overlooked the driveway. Steve, told me he would sit with Errol in his den, and formal living room, they would go for a swim in Flynn’s pool and overlook the entire San Fernando Valley. He would spent time with Errol in the sauna and all Errol would talk about was his films, filmmaking, the dynamics of Hollywood, all the women he met and knew and the most important was his knowledge of ships and of the sea.

CAN YOU IMAGINE BEING 19 YEARS OLD AND HANGING OUT WITH ERROL FLYNN UP AT HIS HOME! TALK ABOUT FREAK LUCK

He eventually got into writing and producered many films such as, Time After Time (1979), Capitol (1982), and Conan the Adventurer (1997).who was an actor, and writer-producer and he still writes westerns. You can see his credits on IMDB

He is the Louie Lamour of England. In the 1950s he met Louis Lamore here in Hollywood and he taught Steve how to write Westerns.

Steve came out to Hollywood in 1949 he lived with Errol Flynn, and Errol introduced him to everyone at his level in the movie business. He even dated Ava Gardner and was close to Marilyn Monroe and Rita Haywood

Steve has written a two-volume book about his time living in Hollywood, called GOOGIES: COFFEESHOP OF THE STARS they are both a great read and he met a lot of these insane Hollywood legends.

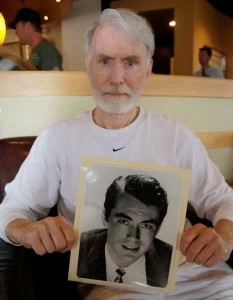

He has been on my Radio show three times and everyone loves his stories. The photo of him was taken when he was in his 80s and the black and white photo was his headshot when he was acting in Hollywood. Steve is a raconteur of old Hollywood, he knew and ran with James Dean and Steve McQueen before they were actors.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY STEVE! IT WAS GREAT TALKING TO YOU TODAY!

— Jack Marino